Nedd Brockmann has never been afraid of death, but five days into his torturous 1,000-mile journey, doubts began to emerge.

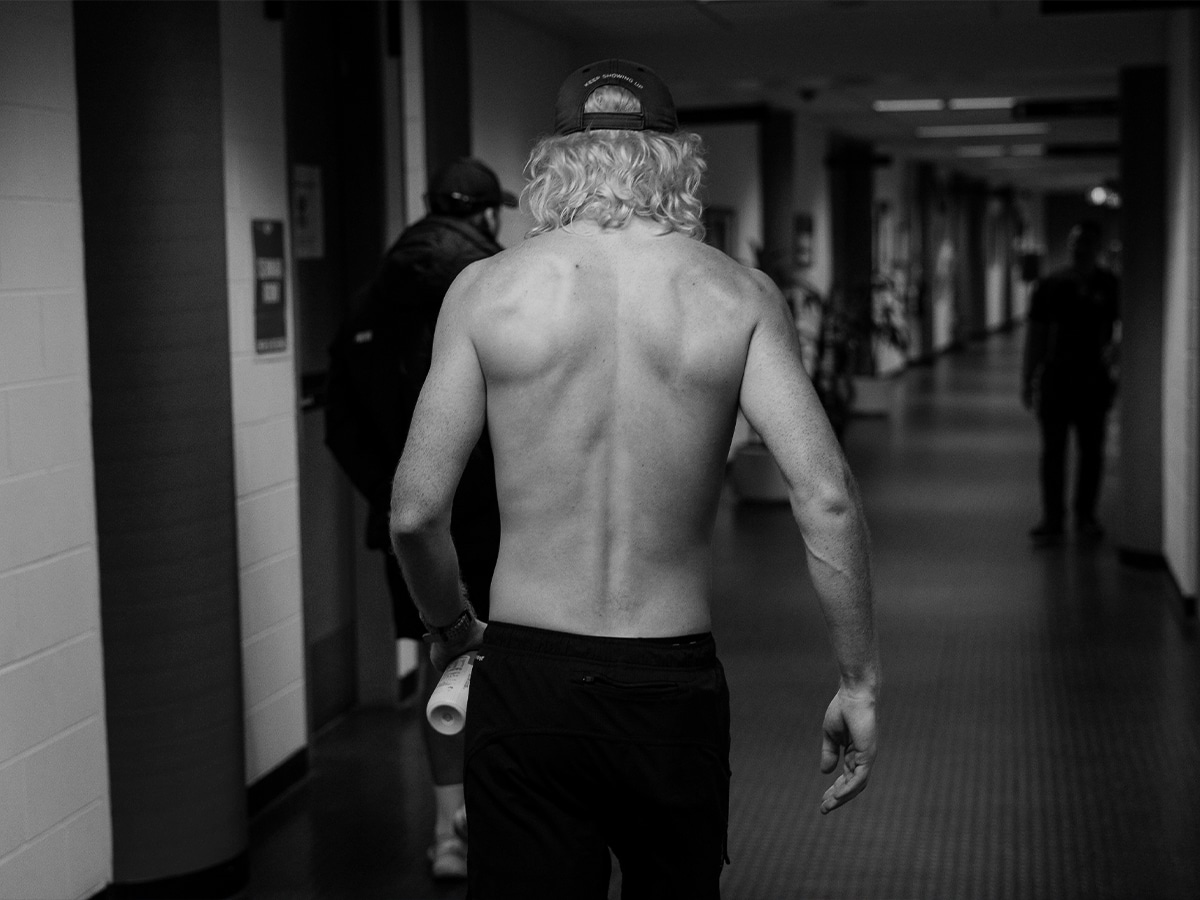

As a thick cover of darkness closed in on Sydney Olympic Park, Nedd Brockmann cut a lonely figure. Battered, bruised but not yet defeated, the 25-year-old tradie turned athlete trudged towards a finish line that was seemingly outpacing him. Try as he might, each begrudging step in his quest to defy the odds and run 1,000 miles in 10 days was proving to be a challenge that even he was not prepared for. With his feet raw, shins aching and blood pouring from his nose, Brockmann could hide it no longer; his body was failing him.

“That was probably the worst I’ve ever felt—it was the closest I’ve ever been to seeing what it might be like to die,” Brockmann says. “My throat was closing up, my nose was bleeding, everything was going to crap. Mum and Belly, my physio, had to make the call and figure out how we were going to go about this because I was going to die out there. I was willing to go to that point, but the team weren’t willing to watch me go to that point.”

Up until that moment, Brockmann had been eyeing Yiannis Kouros’ long-standing ultra-marathon record. The Greek track legend famously ran 1,000 miles in 10 days, 10 hours, 30 minutes and 36 seconds in New York in 1988, and it was this audacious, if not impossible, target that Brockmann set his sights on. A few days into his run, however, it became clear that something wasn’t right.

Regular updates sent to his Samsung Galaxy Ultra Watch across the opening three days revealed that his heart rate was rapidly increasing. Where it had sat at a comfortable 40 beats per minute prior to running, it was bottoming out at 85. To Brockmann, it was just another obstacle in his path to success, but to his team, the medical anomaly represented a much more pressing threat.

“Even when it clearly wasn’t possible at that point to get it (Kourous’ world record), I still hadn’t let that go,” Nedd explains. “The team were like, ‘Nedd’s going to kill himself out here, let’s get a plan sorted’. We had a bit of a moment after dinner on that night five and just said, ‘Okay, let’s just try and get some sleep, try and get six or so hours. It might not be terrible and it might be we’ll be able to hold on and get a pretty solid time.”

Looking back, the decision proved crucial. With his body in agony and feet swollen to three shoe sizes larger than normal, Brockmann was a shell of the vibrant, vivacious athlete who set off on the journey just five days prior. Worse still, he had more than 500 miles left to go.

It’s been two weeks since Brockmann finished up his incredible challenge and life is slowly returning to normalcy for the New South Welshman. When we catch up, Nedd is back to his spritely best—quick with a joke and spry with the kind of cheeky humour we’ve come to expect. It’s nice to see the champ back on top, but even through the playful banter and cheeky smile, the battle scars are plain to see.

“This was the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” Brockmann tells me of his 1,000-mile effort. “It was relentless, it was extreme. I had no reprieve, no freedom of thinking, I had no joy with my team. It was just one of the most insanely hard things. And maybe I wasn’t as prepared as I could have been in order to take this on, and I could have gone maybe 100km a day, but that’s just not what living is about for me. I think if you can go hard at something and go, ‘Well, someone’s done this so I can do it too’.”

“I think you find a lot more out about yourself if you’re willing to chase the extreme.”

A lesser athlete may well have thrown in the towel, but Brockmann wasn’t thinking about his health when he rounded the corner of the Sydney Olympic Park track for the last time. As he reveals, that final day was all about getting his message across, even if it meant dragging his body over the finish line, one limb at a time.

“It’s funny. On the final day, when we had people out in the stands—there was a ‘100km To Go’ sign that came up and everyone started cheering. I was like ‘I don’t think you people understand the enormity of how long 100 freaking kilometres actually is around a track’. That hurt, that was hard to watch. Because I was like, I’ve done 1,500 of these and there’s still 100 to go.”

“Realistically, on a good day, that should take me eight and a half to nine hours, but I was doubling that to get it done, so I knew I still had 16 odd hours to go. Then when the 60km came up, I thought ‘Can we stop putting these ‘To Go’ signs up, it’s starting to freak me out’.

“It’s funny. On the final day, when we had people out in the stands—there was a ‘100km To Go’ sign that came up and everyone started cheering. I was like ‘I don’t think you people understand the enormity of how long 100 freaking kilometres actually is around a track’. That hurt, that was hard to watch. Because I was like, I’ve done 1,500 of these and there’s still 100 to go.”

“Realistically, on a good day, that should take me eight and a half to nine hours, but I was doubling that to get it done, so I knew I still had 16 odd hours to go. Then when the 60km came up, I thought ‘Can we stop putting these ‘To Go’ signs up, it’s starting to freak me out’.

Remarkably, the reality of completing the task didn’t enter Brockmann’s mind until the final half-Master Lap. With around 6km to go, he started to feel the weight lifting from his shoulders, buoyed by the enormous support of a 1,000-person strong crowd cheering him on. As Brockmann reveals, he needed every bit of it.

“With three Master Laps to go, my shin went and I had to strap it up, so I was a bit stumpy-legged, essentially using a crutch,” he says. “I was running on my right, which meant my left arm was just flopping along, but when I saw the sun come up and I hit the end of that Master Lap, I knew. I had half of one to go and I thought even if my legs break and everything goes to crap, I’ll be able to crawl my way home.”

“I just didn’t have any time to switch off; I had no reprieve for 12 and a half days. That last 6km was the first moment of relief that it was going to be over.”

“Just seeing the lineup of people who came out to see me on that final day on video and footage was the most humbling thing. You don’t do it expecting so many people are going to get around it, but when they do, it’s one of the most heartwarming, humbling things you can ever have happen to you.”

Nedd’s time of 12 days, 13 hours, 16 minutes and 45 seconds may have fallen short of a maiden world record, but Nedd maintains he’s “still the fastest to do it since he’s been alive”. And as if averaging 128kms per day wasn’t achievement enough, the homegrown hero’s dramatic run was also beamed across the globe, reaching millions and inspiring a new generation of athletes and advocates. Most important, however, was the impact Nedd’s work had on youth homelessness charity We Are Mobilise.

The Australian-born organisation, which provides outreach, education and direct support for those who have been displaced, was the driving force behind Brockmann’s run. Similar to the 2022 journey, which saw him undertake an extraordinary 46-day run from Perth to Sydney, the 1,000-mile effort was launched to raise much-needed funds. Two years and more than $6 million in donations later, the passion remains close to his heart.

“The fact is we’re all human beings and we all should at least know where our next meal is going to come from, where we’re going to sleep that night, and that we’re cared for,” Brockmann tells me. “That’s one of the great tragedies about it is that not everyone has the same circumstances growing up, and some people don’t have support people to rely on.”

“We’re all human beings but people get looked at differently for being on the street. If someone falls over in Woolies, or on the street, we quickly run and pick them up, but if someone’s there sleeping rough on the street, we don’t go and ask them if we can help or if everything’s okay, we just walk past them.”

To Nedd’s point, youth homelessness remains an issue that is often overlooked in traditional media. The reality of the problem is staggering. Every night across Australia, one in two children and young people are turned away from crisis refuges, due to a shortage of beds and a lack of youth-focused support. With organisations such We Are Mobilise, building awareness is rising, but as Nedd explains, the solution to Australia’s burgeoning homelessness problem is far more nuanced.

“I think homelessness in general is something we all need to help and mobilise,” he says. “We’re doing amazing work and working with great organisations. It’s not trying to be mobilised through changing—it’s trying to be an instigator to help everyone else to make sure we can exponentially grow the resources to help people living rough.”

In his mind, homelessness demands action and the word ‘immediate’ doesn’t do the urgency of the problem justice. The moment he completed the 1,000-mile trek, the 25-year-old went straight into PR mode, launching the second phase of his Uncomfortable Challenge. Alongside major partner Samsung, who provided the athlete with Buds3 Pro to listen to music during his run, Brockmann used his platform to encourage others to follow suit, albeit in their own unique way.

“I didn’t sleep for the first seven days really after I finished. So I’m tweaking out, trying to work out, doing my knee, and then we started the Uncomfortable Challenge seven days later,” he tells me. “At that point, everyone was doing their own challenges and I was getting around that, trying to see people.”

As with seemingly all of his endurance battles, the aptly named Nedd’s Uncomfortable Challenge captured the cultural zeitgeist. Across the globe, everyday people joined the cause, pushing themselves to their physical, mental and spiritual limits, all in the name of humanity. It was, to put it lightly, a movement of epic proportions.

“We had 25,000 people sign up and take part, which is, for me, just mental. (We raised) Over $2 million for them, in addition to the $2.7 million that we were able to raise as part of the run. Ideally, in the next five years, this thing’s in the nation’s psyche, and we’ve got people going nuts in October, going, “Let’s get behind this, let’s do something hard and raise money for good’.”

Listening to Nedd speak, two things become immediately apparent. The first is that the 25-year-old tradie is wise well beyond his years, able to so effectively through the cultural divide with common sense. He isn’t political by nature, but rather a man who believes deeply in humanity and his no-nonsense approach is strikingly refreshing. The second is that he isn’t afraid to be vulnerable.

In our discussion, Brockmann ebbs and flows effortlessly between jokes and anecdotes, but when the conversation sweeps to more pressing themes, he recognises the gravitas. In fact, it’s become somewhat of a trademark.

Throughout his incredible 1,000-mile challenge, Brockmann was brutally honest about the physical and mental tolls that presented themselves each and every day. In one emotional statement to fans posted at the height of his mid-run exhaustion, the athlete revealed that the only constant that pulsed through his mind during the challenge was the ‘surety of death’.

“I would probably think about that five times a day, which a lot of people might look at as a negative, ‘Oh, you’re so sombre, stop talking about death’. But I actually think it’s quite relieving. It’s quite freeing,” he tells me.

“The freeing nature of that is that you either sit back, get upset and waste your life, or you get up, get after it and make the most of it. Having that in the back of your head constantly is quite a nice reminder that you should go and do it.”

“That’s the beautiful thing about life: the sun’s going to keep going up and it’s going to keep going down, regardless of what you want.

“You should go and do the thing because people were planning on waking up today and they didn’t. People were planning on going to work, and they didn’t. I think you should never, ever wait.”

Brockmann lets his words hang in the air just long enough for me to comprehend the earnestness of his statement. As we’ve learned over the past two years, it’s not a gimmick or an act—Brockmann believes wholeheartedly in his cause. Having watched him take his body to the extreme and learning of the enormity of his achievements, it’s impossible not to be moved. I suspect that’s precisely the point.

In many ways, Brockmann has become the anti-celebrity—someone who rejects the nature of fame in order to prioritise his message. To him, it isn’t about ‘playing the game’, but rather seeing the influence transform into action. He may well have famous friends by his side now, but Nedd’s goal was never to become a star. He simply wants to leave this world a better place than how he found it and as he rightly explains, progress only starts when you put one foot in front of the other.

Credits:

Words: Nick Hall

Images: Samsung, Marty Rowney/Bursty, Bradley Farley Photo, Puma

Special Thanks: Ogilvy, Samsung

Comments

We love hearing from you. or to leave a comment.