Australia’s black summer of bushfire devastation has focused new attention on Australia’s emission reductions track record and whether the needed reductions are being made.

On one hand, Prime Minister Morrison has proudly declared that Australia “is right out ahead” and doing “the heavy lifting” on emission reductions. And as he has repeatedly claimed, Australia will “meet and beat” its Paris Agreement target of reducing emissions by 26-28 per cent on 2005 levels by 2030.

On the other hand, Australia was recently rated as the worst-performing of 57 countries, on climate protection performance, in the independent Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) 2020 report. In Australia, a range of expert bodies are also calling for stronger action, including the Australian Academy of Science which recently warned that “Australia must take stronger action as its part of the worldwide commitment to limit global warming”.

Who should we believe?

After the recent extreme weather events, one thing is clear; More and more of Morrison’s own “quiet” Australians are now questioning whether Australia is doing enough and shouldering our fair share of global efforts to limit global warming.

It’s therefore timely to look at the real facts on Australia’s emission reductions and on where the Morrison Government is heading.

Are Australia’s Emissions Actually Coming Down?

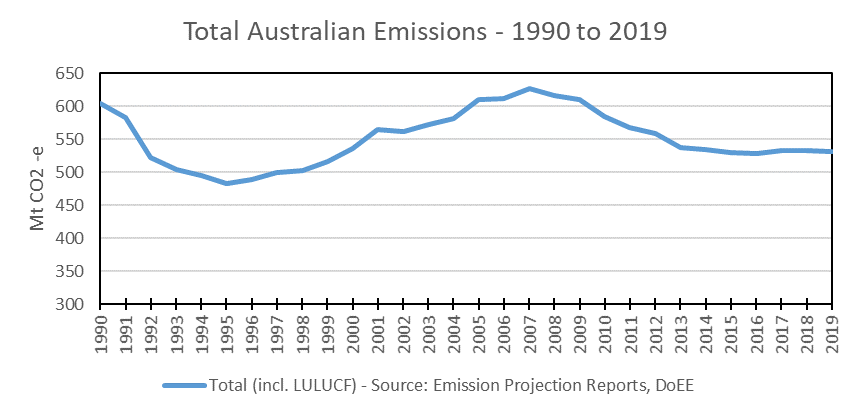

Despite Government claims that emissions are currently falling, Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory data shows a different picture. Australia’s total emissions have NOT been coming down in recent years. Emissions in 2019, in fact, were at the same level as in 2014.

As seen in the chart below, however, following steady rises from 1995 to 2007, emissions did fall from 2007 to 2014 by around 15%, in part due to a fall in the demand for electricity and a shift in electricity generation towards renewables.

Total emission trends since 1990, however, hide the real picture on underlying emission reductions due to actual government policy and action.

By far the biggest single sector impact on Australia’s total emission trends since 1990 has been from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) emissions.

In 1997, the government lobbied hard and successfully internationally to get LULUCF emissions included in Australia’s overall emissions count, given they would greatly enhance Australia’s performance against what were moderate Kyoto Protocol emission targets.

In 1990, for example, LULUCF emissions, largely from land clearing and deforestation, accounted for around 22% of total emissions reported in the National Inventory. By 2019, the LULUCF contribution had turned into an actual 3.4% reduction in total emissions, due principally to a significant decline in land clearing and deforestation.

The trend in Australia’s emissions from 1990 to 2019 and the official projection to 2030, as reported in the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory and in the Emission Projections 2009 report from the Department of Environment and Energy (DoEE) are set out in the chart below.

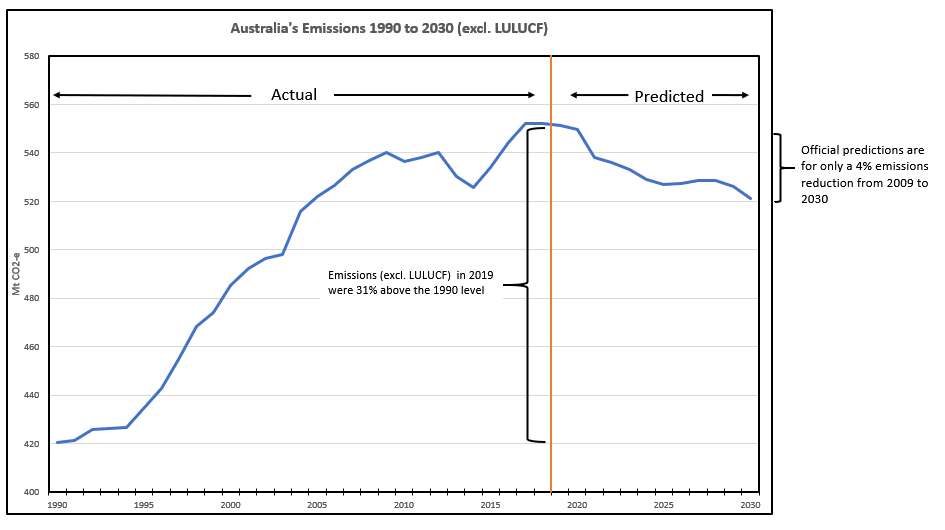

Australia’s Emissions Excluding Land-Use Change & Forestry

When the LULUCF impacts are excluded, Australia’s emissions in 2019 were 31% above the 1990 level.

Further, emissions (excluding LULUCF) are officially predicted to decline by only 4% between 2009 and 2030, based on current government policy settings.

Source: Australia’s Emission Projections, 2019, Department of Environment and Energy

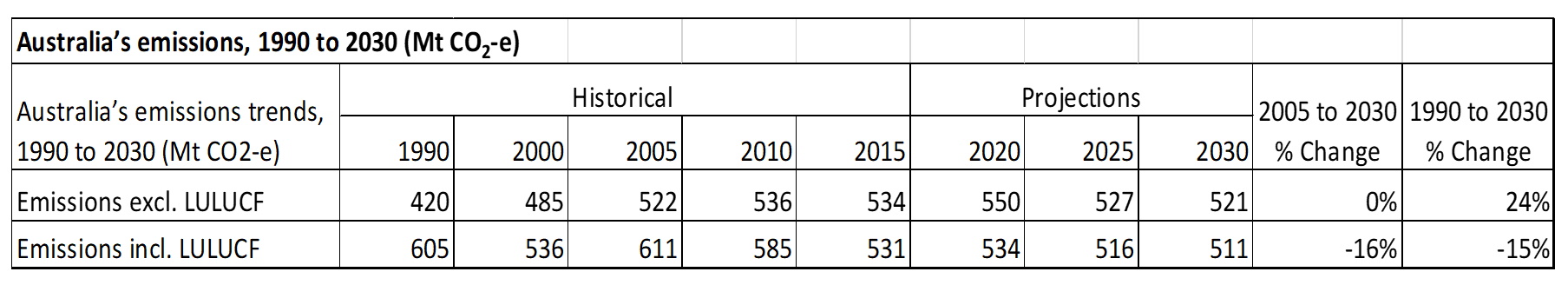

In fact, as seen in the table above, emissions for 2030 (excluding LULUCF) are officially projected to be still some 24% higher than 1990 levels, with no reductions expected in the 2005 to 2030 period.

Is Australia’s Commitment to the 2030 Emission Reduction Targets a “Fair Dinkum” One?

Australia signed up to the Paris Agreement in December 2015 and committed, unconditionally, to reduce its emissions by 26% to 28% below 2005 levels by 2030.

The Paris Agreement Explained

The Paris Agreement is important as it is the global framework under which countries have agreed to take action to hold the average global temperature increase to well below 2°Celsius, and to pursue efforts to keep global warming below 1.5°Celcius compared to pre-industrial levels.

Under the Paris Agreement, countries also generally share a common goal to hit net zero emissions by 2050, although the Morrison Government still refuses to sign up to such a goal, despite all State Governments having net zero-emission goals.

All the 185 signatory nations could choose their own emission reduction targets and use a self-selected base year.

Australia decided to choose 2005 as its base year. Australia’s 2015 emissions were already 13% below 2005 levels when the commitment was made and, given that 2005 emissions were close to the peak emissions for Australia, the target reductions looked much larger relative to other potential base year choices.

But, according to official emission projections, the Morrison Government will still NOT “meet or beat” Australia’s Paris Agreement targets, based on current policy settings.

Australia’s Emissions Projections 2019 report clearly states, “emissions are projected to decline to 511 megatons of CO2 equivalent (Mt CO2 -e) in 2030…from the 2005 level of 611 Mt CO2 -e… which is 16 per cent below 2005 levels”.

That is, Australia’s 2030 emissions are currently officially projected to be only 16% below 2005 levels, well short of Australia 26% to 28% Paris Agreement commitments.

Official projections also reveal that emissions in 2030 are only expected to be 4% below the actual 2019 emissions level (refer again to the second chart above).

What’s Really Happening with Australia’s Paris Agreement Commitment?

How can the Prime Minister repeatedly claim that Australia will “meet and beat” the 26-28% target, given the official projection that emissions will only be 16% below 2005 levels in 2030?

The answer lies in the Government’s unilateral decision to change to the Paris Agreement rules and apply creative accounting, which effectively reduces Australia’s Paris Agreement targets.

In simple terms, the Government has decided to count what it calls ‘overachievement’ against Australia’s emission allocations, dating back to 2008, as future emission reductions towards Australia’s Paris Agreement target.

Australia’s emission targets in the 2008 to 2020 years were in summary:

- 2008-2012: an 8% increase in emissions, compared to 1990 levels in the first Kyoto Protocol Commitment Period;

- 2013-2020: a minimal 0.5% emission reduction on 1990 levels in the second Kyoto Protocol Commitment Period; and

- 2020: a 5% emissions reduction below 2000 levels by 2020, as part of the 2010 Cancun Agreement.

Even though 2020 emissions are now officially projected to be just 0.4% below 2000 levels – well less than the 5% reduction target – and emissions actually rose in the 2008 to 2012 period, the Government is claiming an estimated 411 Mt CO2 -e of ‘overachievement’.

The Government’s claimed ‘overachievement’ is large, equating to some 9 times the annual emissions of all the other Pacific countries combined, including New Zealand.

By counting these expired ‘overachievements’, from up to a decade ago, as quasi emission reductions against the Paris Agreement targets, the Government is lowering Australia’s actual 2030 emission reduction task to just 15% to 17%, based on the official Emission Projection 2019 report data.

Consequently, the Morrison Government has ‘rewritten’ Australia’s unconditional Paris Agreement commitment of a real 26% to 28% emission reduction by 2030 on 2005 levels, and reduced it to just 15% to 17%.

Why Lowering Australia’s 2030 Targets Makes the Future Task More Difficult

All the talk about needing to cut emissions is based on the reality that the world has a certain amount of cumulative emissions that it can emit, called its carbon budget, before the thresholds of 1.5 Celsius and then 2 Celsius becomes inevitable. Australia also has a carbon budget for the maximum amount of emissions it can emit if it is to hit emission targets.

By counting the expired ‘overachievements’ as quasi emission cuts towards the 2030 targets, Australia will exceed its carbon budget for meeting its Paris Agreement commitments. The carbon budget can only be met by making real cuts.

As a result, future emission cuts will need to be deeper, which means it will be harder to ultimately get to a zero net emissions future so as to prevent even more dangerous global warming.

Hence, the reason the Government’s lowering of Australia’s Paris Agreement targets is of such concern.

Can Australia’s Emission Reduction Have a Meaningful Impact?

The Morrison Government has argued that as Australia is only responsible for about 1.3% of global emission, we can’t have a meaningful impact.

Would the Government say the same about Australia’s contribution in World War II, where the one million Australians that fought represented less than 1.5% of the total allied and axis forces that served?

Australia is, in fact, the world’s 14th largest emitter (larger than the UK, Italy and France for example). And when Australia’s current coal, oil and gas exports are added, Australia’s contribution is around 5%, or roughly 1/20th of the global climate emissions footprint.

With only 0.3% of the global population, Australia ranks amongst the highest per capita emitters – nine times higher than China’s, four times that of the US, and 37 times that of India. While emissions per capita have come down recently, this has largely been driven by increases in Australia’s population rather than emission reductions.

The fact is, countries with emissions less than or equal to Australia, currently account for around 28% of global emissions in total. If all these countries individually adopted the Morrison Government’s view that they can’t have a meaningful impact on global emission, then the world has little hope of preventing even more dangerous global warming.

Irrespective, Australia punches well above its size in global influence, and it is looked upon for leadership on global issues such as climate change.

The Summary Facts

The following summary has been derived directly from Australia’s National Inventory of Greenhouse Gas Emissions data and the Government’s own official Emission Projections and is totally fact-based:

- Australia’s total emissions have NOT been coming down in recent years. They have flatlined since 2014.

- The Morrison Government is NOT on track to “meet or beat” Australia’s Paris Agreement commitment to reduce its actual emissions by 26% to 28% below 2005 levels by 2030.

- The Government has lowered the targets for actual emission reductions to just 15% to 17% below 2005 levels by 2030, through its decision to count expired ‘overachievements’, from over a decade ago, as quasi emission reductions towards Australia’s Paris Agreement targets

- The latest official predictions by the Government’s Department of Environment and Energy (DoEE), are that total emissions in 2030 will only be 16 per cent below 2005 levels.

- Official projections also reveal that emissions are only expected to fall 4% below 2019 levels over the next decade to 2030.

- Excluding the emission reduction benefits from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) Australia’s current emissions are some 31% higher than they were in 1990; and

- Official projections are for Australia’s emissions in 2030 to be still some 24% higher than they were in 1990 (excluding LULUCF), with no reduction expected on 2005 levels.

The Wrap Up

Based on the above facts, Australia is clearly underperforming in its emission reduction efforts and is not carrying its fair share of global efforts to limit global warming.

Unfortunately, there is also a broader lack of adequate global emissions reduction progress. This has triggered the United Nations, in its Emissions Gap Report 2019, to recently warn that global temperatures are now on pace to rise as much as 3.2 degrees Celsius by the end of the century.

As a stark wake-up call to member countries, the UN report concluded that from now, global greenhouse gas emissions must begin falling by 7.6% each year, if we are to limit global warming to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius. The report also warned that any increase beyond 1.5 degrees will result in “even wider-ranging and more destructive climate impacts”.

But with the 2019 average global temperature 1.1°Celsius above that of the late 19th century, the world is already well on the way to this dangerous 1.5 degree warming threshold.

Added to this, Australia and the world are currently nowhere near the 7.6 % emission reductions needed each year if we are to limit global warming to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Recently, the Energy and Emission Reductions Minister, Angus Taylor, advised that “when you hear someone say they are ashamed to be Australian because of our emission reduction performance, point them to the facts”. We couldn’t agree more that people should look at the facts and draw their own conclusions.

Article by Dr Noel Purcell

Dr Purcell has been actively involved in climate change initiatives, both domestically and through global initiatives, since the early 1990s. He was involved in the formation of the United Nations Environment Program Financial Initiative (UNEPFI) and the establishment of the Equator Principles to manage environmental and social risk in project financing. He was a driver of the Business Roundtable on Climate Change initiative and has been a member of the Climate Project initiative.

Comments

We love hearing from you. or to leave a comment.