Published:

Readtime: 11 min

Every product is carefully selected by our editors and experts. If you buy from a link, we may earn a commission. Learn more. For more information on how we test products, click here.

“The life of a distiller,” says Miles Munroe. We’ve just popped the trunk of his green Pathfinder to discover a small sample bag of malted barley, which seems to have appeared from out of nowhere. Four days later, the same trunk will hold two buckets full of Oregon hazelnuts, hand-picked off the grounds of Dominio IV vineyards in the Willamette Valley. His plan is to roast the nuts and then soak them in signature Westward whiskey just to see what happens. When asked whether the natural oils of hazelnuts might mix with the spirit and thereby hinder the results, he smiles and replies, “I guess we’ll find out.”

This is par for the course for Munroe, Head Distiller at Westward Distillery and a man of many passions, talents, and tastes. You’d recognise him as such at first sight. Standing over six feet tall, he rocks long wavy brown hair with streaks of grey, groomed sideburns, illustrative tattoos, a walrus moustache, septum nose ring, and smoky eyes. When dressed for an event, his attire veers toward a Western or Southwestern theme—picture a dark blazer over a patterned button-down, with a bolo necktie, slim-fit pants, and a cowboy belt. He’s the kind of dude who wears brown leather shoes whilst traversing the occasionally steep and rocky terrain surrounding Timberline Lodge near the top of Mt. Hood. Regarding this peculiar choice of footwear for a hike, he proclaims in a raspy but energised voice, “That wasn’t a hike!”

At home, Munroe collects VHS tapes of cult movies, post-punk and dark wave records, and other ephemera. In his free time, you might find him attending all-night horror movie marathons at Portland’s Hollywood Theatre, spinning vinyl at a local Portland bar, hanging out with a broad network of fellow drinkers and hobbyists, or hitting up watering holes of every variety throughout the Pacific Northwest. Otherwise, he’s plying his trade at the Westward barrel house and travelling around the world to spread the word about American single malt whiskey. We guess he’ll sleep when he’s dead.

Invite Munroe to do, try, or taste pretty much anything and he doesn’t say “yes,” he says “absolutely.” It all feeds into what one might deem an insatiable sense of openness and curiosity, the same that he brought to the respective worlds of wine and beer before arriving at Westward’s door. Yet no matter how wild his experiences or experiments, an underlying consistency persists. Call it the Westward way.

Beer All Grown Up

Before Munroe came aboard as Head Distiller, Westward co-founder and Master Distiller Christian Krogstad blazed a similar trail through the worlds of wine and beer. To spend a little time with Krogstad is to get the sense of an open and ambitious personality who’s always willing to push himself into new modes of craftsmanship, either at work or at home on his farm. He discovered the connection between beer and whiskey whilst working as head brewer at the Pacific Northwest institution McMenamins, where they also make spirits. So began the next step of his career, with the opening of House Spirits in 2004.

Whilst focused on whiskey, House Spirits made everything from rum to aquavit to vodka during the early days of production. They also crafted a little side hustle by the name of Aviation American Gin, which was then purchased by actor Ryan Reynolds and Davos Brand (who later turned around and sold it to Diageo). As a result, Krogstad was able to build a new distillery in the heart of Portland, with the exclusive goal of churning out American single malt whiskey.

From the very beginning to now, beer-making empowered both the philosophy and production process at Westward. “We make beer—we just take all the water out,” says Munroe during a distillery tour. To elucidate, he repeats the brand mantra that their product is “brewed like a pale ale, made like a single malt, and aged like a bourbon.”

Specifically, a trio of barley is locally malted and then delivered to the distillery, where it’s stored in a grain silo. First comes the milling process, during which the grain is split open to expose its flavourful innards. Water is mixed in and the sugar is extracted and pasteurised before arriving in one of the distillery’s tall steel fermenters. During the slow fermentation that follows, added yeast eats away at the sugar to produce alcohol, which at this point is known as the “wash.”

“How many distilleries let you taste their wash?” Munroe asks us whilst tapping the fermenter like it’s some sort of massive keg. The liquid that pours out is uncarbonated beer and tasty beer at that, with a fruity and floral character. Were the brand to run it through hops, carbonate it, and then bottle it up, they’d be one amongst a number of Portland’s many high-quality brewers. But alas, this journey is just getting started.

Grain and Fermentation Over Oak and Time

In the next room over, a custom-built still converts the recently fermented beer into whiskey. Unlike most stills, this one features a rotund main frame and short copper neck. As a result of its unique design, the evaporating droplets stay closer to the source and hence closer to the liquid’s core flavours as they migrate upward, making their way into a smaller still for a second round of distillation.

Diluted to 62.5% ABV, the whiskey is then sent into new American oak, which has undergone heavy toasting and a light char. The juice will rest inside the barrel for anywhere from 4.5 to 7 years before being blended with its brethren and then bottled in its natural colour. Those age statements might seem relatively young by most single-malt standards, but the proof is in the proverbial pudding. By making calculated (and purposefully inefficient) decisions during production, Westward is able to generate a seriously distinctive and remarkable profile in as little as three years’ time.

How do we know? Because we visited the brand’s barrel warehouse—aka “Jenny”—and sampled their juice at the respective ages of zero, one, two, and three. Even after just three years, the whiskey has absorbed enough oak to offer an expert balance between flavours of tropical fruit, black pepper, wood spice, and stout. And whilst the brand emphasises the importance of high-quality grain and fermentation over oak and time, their use of virgin oak certainly goes a long way (when compared to the ex-bourbon barrels used by most Scotch distilleries) in terms of maximising flavour.

A Growing Movement

If there’s a missing piece to the puzzle, his name is Thomas Mooney. Westward’s co-founder and CEO, Tom layers his sharp mind and adventure-ready attitude beneath a somewhat boyish disposition, making him effortlessly approachable and eager to answer any question you can throw his way. Whereas Munroe and Krogstad are no strangers to marketing or networking (they seem to know just about everyone in the spirits industry), it’s Tom who is helping turn American single malt whiskey into a full-blown movement.

For example, Westward was one of the first (and founding) members of the American Single Malt Whiskey Commission. What began with a collective of nine distilleries is now over 100 members strong, with representation all across the country. Taking a few cues from Scotland, the commission is hoping to preserve a certain amount of integrity and reliability amongst America’s single malt providers. To that end, they’ve put forth a liberal set of standards, namely that American single malt whiskey must be made from 100% malted barley, distilled entirely at one American distillery, and bottled at a minimum of 80 proof.

Crafted in America perhaps, but Westward is also exploding across the world stage. They retain a major presence here in Australia and are rapidly penetrating markets in places such as South Korea and Germany. With their success comes the potential for an entire sector of American single malt whiskey, which exists in a flavour class of its own.

A Shifting Climate

With its wet falls and winters and hot, dry summers, the Pacific Northwest is an ideal place to grow barley or make beer, wine, and whiskey. But as the last few years have gone to show, dependable weather and fertile soil are certainly no guarantee. Even as their momentum surges upward, Westward continues to deal with more than one kind of climate shift.

In 2020, the global pandemic hit the brand particularly hard by essentially halting restaurant sales and shutting down the tasting room, two major revenue streams. That same year, the entire Pacific Northwest was scoured in wildfires and toxic smoke for five days in a row. Had the raging Estacada fire expanded just a few miles further, it would have burned down Westward’s barrel warehouse and thus their entire whiskey supply.

Climate problems persisted into the summer of 2021 when temperatures climbed as high as 116 F (46.7 C), smashing previous records. Then in mid-April of this very year, a freak snowstorm and its adjoining frost caused significant crop damage to the local wine industry amongst other things.

Facing these types of changes and challenges, Westward has learned how to roll with the punches. They launched a wildly successful membership club, for instance, which offers exclusive access to limited edition releases such as the acclaimed Elements Series, along with other benefits. They’re also racking up more attention, acclaim, and awards than ever before, making them less reliant on the kind of variables that another pandemic will surely disrupt.

Consistency Meets Creativity

In just under two decades, Westward has become one of the foremost names in American single malt whiskey and one of the most important distillers in all of the Pacific Northwest. At the heart of their output is a silky spirit with a light effervescence, which rides in on notes of tropical fruit, malted barley, black pepper, raisin, vanilla, and dark chocolate before trailing out on waves of oak spice and stout beer. However, don’t take a consistent flavour profile to mean that these folks rest on their laurels.

On the contrary, Munroe appears absolutely tireless in his pursuit of permutation. Whilst he and Krogstad have relegated distilling duties to a team of experts, one can still find him trading barrels and ingredients with an array of local wine, beer, and spirits producers, or performing all kinds of crazy experiments inside the warehouse. Most of these experiments take the form of different cask maturations and not just the pinot or stout cask statements that make up part of the brand’s core line-up. During our visit, we sampled whiskey that had been sitting in barrels previously used for everything from chardonnay to Sirah port to Mezcal.

If you notice the absence of a sherry cask finish, that’s no accident—Munroe and Krogstad remain defiant in their resistance to the ubiquitous trend (though we have a feeling they might eventually give it a go). They also migrate well outside the art of finishing by occasionally crafting whiskey from unique strains of barley. That includes Oregon-grown Full Pint Barley, which brought dense notes of honey and floral accents to Westward’s familiar profile. And when something doesn’t work—such as one particular project involving the use of non-traditional oak barrels from a local provider—they move on to the next experiment.

It all goes to show that the foundational use of 100% malted barley can lead to a broad spectrum of aromas and flavours as the American single malt movement continues to grow. Just as in Scotland, certain rules and regulations are being proposed and implemented so as to discourage fraudsters from slapping distinctive labels on any old swill, but not to the point of kneecapping creativity. Speaking of different flavours, would this be a good time to mention that we have our own limited edition (and frankly delicious) single-barrel collaboration with Westward? You can purchase it here.

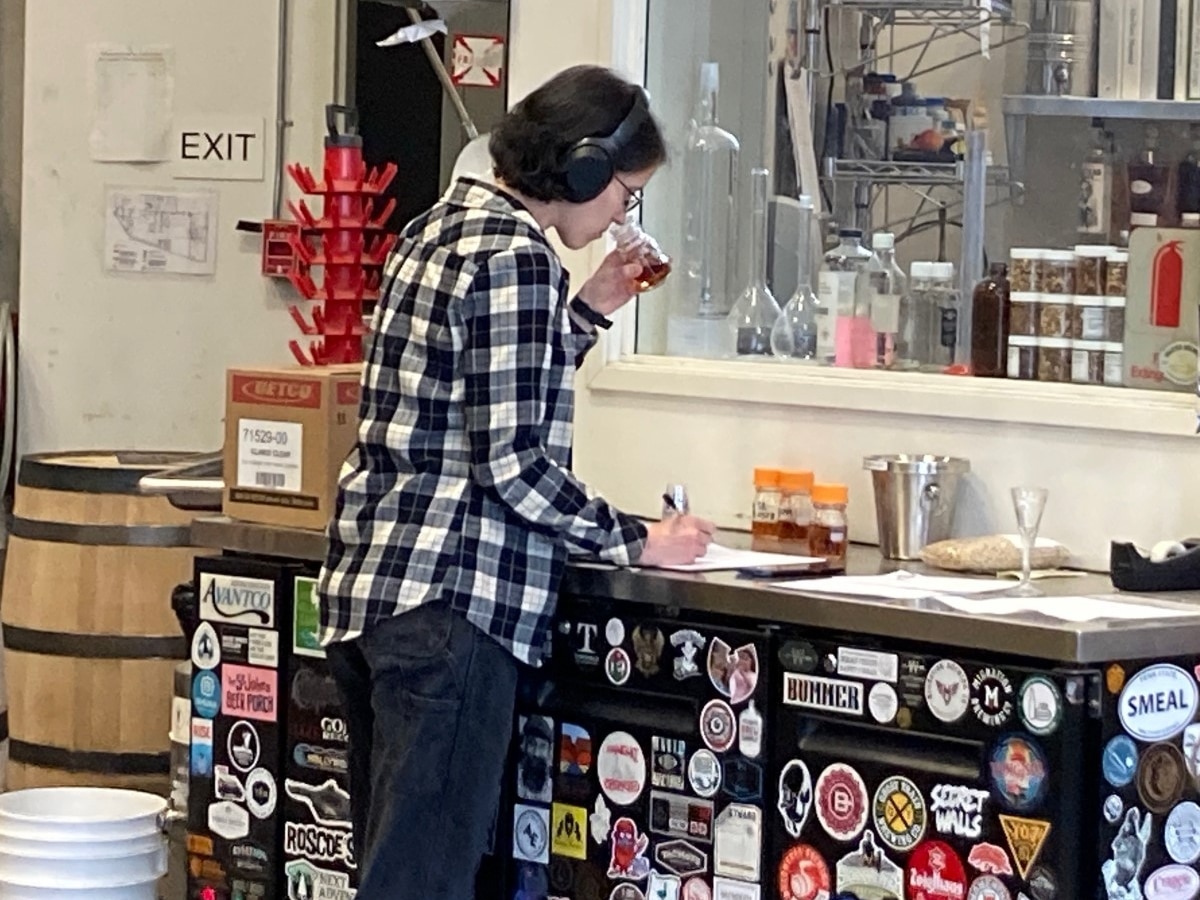

Meanwhile, Westward’s operation would be nowhere if it wasn’t for a diverse and ever-expanding team of distillers, managers, millers, tasters, labellers, cleaners, technicians, pourers, drivers, and marketers. At the distillery, a young woman wore noise-cancelling (i.e. sensory-depriving) headphones whilst sampling a fresh batch of whiskey to ensure consistency and quality alike. Mere yards away, a small group applied a portion of the bottle label by hand. Putting an emphasis on every spare detail, this is modern production done right with excellent taste to match. It’s also the opening of an exciting new chapter in American whiskey. Go Westward indeed.

Comments

We love hearing from you. or to leave a comment.