Published:

Readtime: 12 min

Every product is carefully selected by our editors and experts. If you buy from a link, we may earn a commission. Learn more. For more information on how we test products, click here.

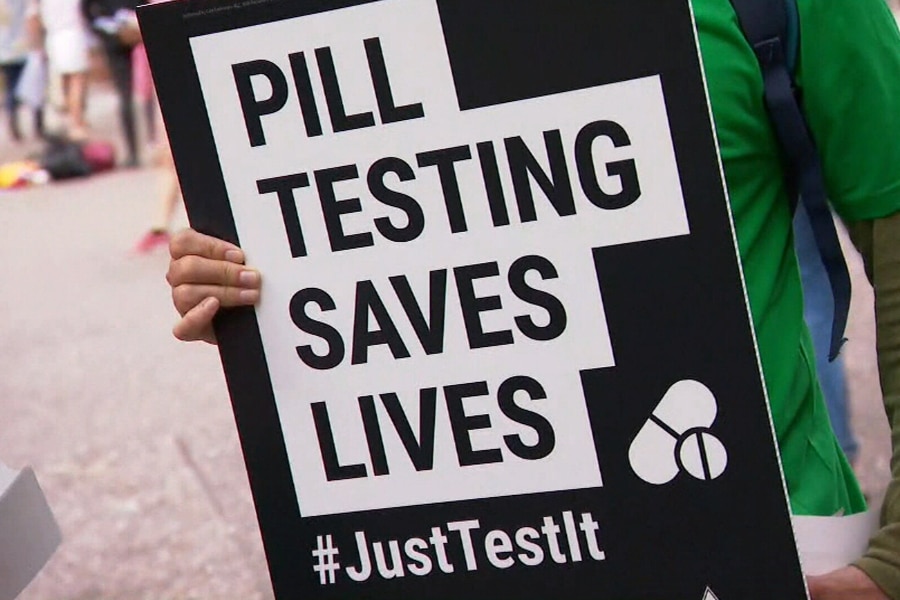

For a generation that, to steal from their own vernacular, froths on a sizzling summer music festival, there is a very real and very hotly debated topic currently raging in Australia about whether or not we should introduce pill testing at large events, in an attempt to quell the number of people who die from accidental drug overdoses.

The debate surrounding pill testing in Australia may feel like it’s hit terminal velocity, but it’s a very important one, because it is, potentially, one of the first steps for our state government in NSW to take in acknowledging recreational drug in the hope to minimise harm.

Currently, both sides of the fence have very impassioned opinions on the subject, and both make very valid arguments. On one hand, harm reduction is, by all means, a no-brainer, and that anything that has been tested and proven to prevent death is a good idea, whether you think people should be taking drugs or not.

The other side, currently adopted largely by the NSW Government and state law enforcement agencies, suggests that by testing an illicit substance, the state would be condoning its use, or suggesting in some way that it is safe. This is a rational point too, as many fear that an overdose on something that has been tested could then lead to accountability on the part of whoever tested it.

Others will posit that taking a hard line against something that is supposed to be a bit of fun used by reckless kids is never going to work, because, well, it’s fun and they’re kids. Historically, a higher police presence hasn’t changed a thing, and some argue that it has, in fact, made matters worse, as young festival goers are more likely to swallow whatever drugs they have at the sight of a sniffer dog for fear of being caught and charged.

Wherever you stand, though it’s a new issue for our shores, other countries have long-implemented practices in place to deal with the matter. It has been legislated as a part of drug policy in the Netherlands since 1992. Services supported by the Government in Austria have existed since 1997.

Switzerland followed suit in 2001, and Belgium also has a policy in place allowing for this.

Pill testing is also available in Spain, France and Portugal, and not-for-profit organisations have tested pills in the US and Canada since the late ’90s.

Even the UK and New Zealand now allow for pill testing–one of the many reasons that frustrated supporters of the issue are arguing that Australia is well and truly behind the times.

You’ll also like:

- INTERVIEW: Javier Peña and Steve Murphy, The Real DEA Agents of Narcos

- Australia’s Sewers Reveal Illicit Drug Trends

- Why Changing Australia Day Is Not The Worst Idea

Why do People Take Pills?

This may seem like a silly question to many, but the reasons for taking pills are the cause of this debate in the first place.

In short, ecstasy tablets have been a staple on the party circuit for a long time. From the rave days of the ’90s to the club days of the ’00s to now, when the almighty outdoor festival, Indian headdresses, henna tattoos and all, reigns supreme.

The active compound in MDMA gives the user a long-lasting feeling of euphoria (they didn’t call it ecstasy for nuthin’).

Why are Pills Dangerous?

Though statistically, the records of overdose and death are low in comparison to the number of users, MDMA can be very dangerous, for many reasons.

The active ingredient in ecstasy is 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine, or MDMA for short. While MDMA capsules are common amongst users today, most people will know of pills (or pingas, we’re an Australian publication, after all) as tablets that contain MDMA, often mixed with other agents.

MDMA is a contentious compound. It has been widely tested and experimented with, and though some scientific studies have returned optimistic results with regards to its carefully monitored and controlled usage being useful in treating depression, amongst other things, the notion of its use in a medical context is still in its nascent days.

MDMA is potent, and overdose can occur, with different people being able to handle different amounts of it. One of the reasons taking pills can be dangerous is that it’s near impossible to know the exact amount of MDMA in a pill. Methamphetamine can be often fatal by themselves.

Another factor is that there’s also no way of knowing just with what exactly the MDMA has been “cut”. It is important to note, however, that most recent fatalities were a result of people taking too much or overdosing on ecstasy, rather than due to any specific nasties in the pills themselves. In other words, no drugs should be ever be considered completely safe.

Dangerous additives are still rife in illegal pill production, and many of them can cause severe adverse reactions. A recent trial at Canberra’s Groovin’ The Moo festival last year found that out of over 70 samples tested, only around half actually contained pure MDMA, as the owner of the pills had thought.

One test revealed the incredibly dangerous N-Ethylpentylone (ephylone), which has been linked to many overdose deaths around the world, and other nasties that turned up during the testing trial included arnica (a muscle rub), Hammerite paint (a spray paint used on metal), as well as a Polish brand of toothpaste (perhaps not deadly, but very, very weird).

What is Pill Testing?

Pill testing involves an independent body setting up shop at a festival, usually in a tent; not dissimilar to a food truck or bar. Though deliberately more discreet than other vendors, punters can go to the tent with drugs that they have illegally obtained, and in a safe environment have them tested by a machine operated by a trained professional, who can then advise them on what exactly it is they have.

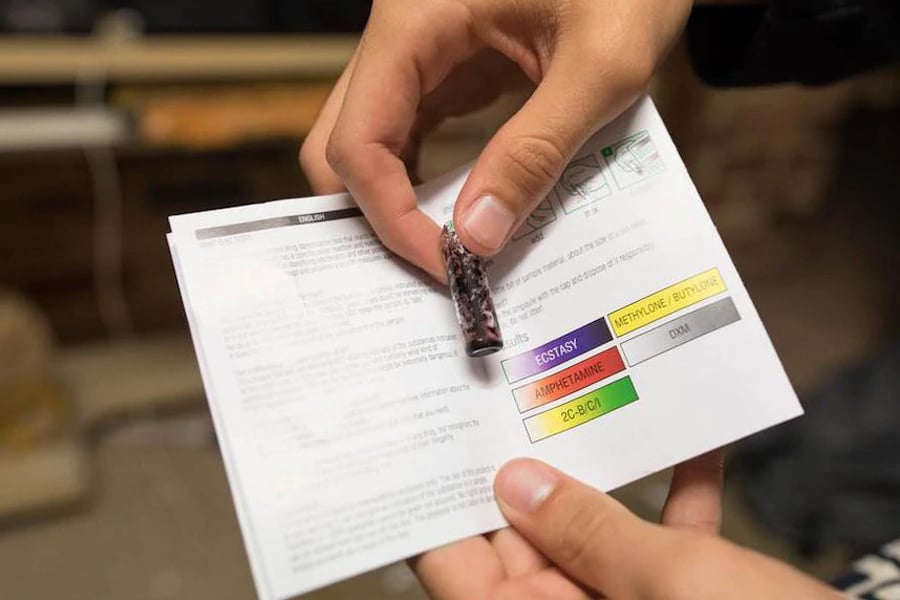

People who go to pill testing tents are first asked what they think it is they have, before scraping a tiny sample onto a plate (the tester never touches the pill themselves), about the size of a pinhead.

The sample is then put through an infrared spectrometer, to test for chemical compounds, and, to some extent, the volumes in which they are represented. The volunteer at the booth will then inform the owner of the pill what has been found.

Pill users who have their drugs tested are then advised that there is no safe way to take illicit drugs and that there is no guarantee that what they have is safe for consumption. No pill testing station advises the user on purity, or “quality”, if you will, of the substance they have obtained; merely of its presence, and the risks associated with its ingestion.

What is the Pill Testing Process?

During the recent trial at Canberra’s Groovin’ The Moo festival, the (quite simple) process goes thusly:

- People in possession of substances they want tested queue at the pill testing tent, in the medical precinct of the festival.

- Upon entering, festivalgoers are presented with a waiver to sign; this releases the pill testers from any liability.

- Educators inform attendees that the test doesn’t guarantee the safety of the drugs, firmly reiterating that there is no wholly safe way to take illicit drugs.

- Attendees provide a small sample of their drugs to a chemist who takes a photograph, weighs it, and places it (the sample) in the infrared spectrometer. A laser is blasted through the tiny sample, which sits atop a diamond. The chemist can analyse what is inside the sample based on the reflected light.

- Whoever provided the sample is informed of the results, and, once again, informed that there is no safe way to take illegal drugs.

- Lastly, the user is given an armband to indicate that their substance has been tested.

How Does Pill Testing Reduce Harm?

One of the biggest dissenting arguments is that, by advising somebody of the contents of their drugs, the testing body is somehow condoning its use.

In reality, the testing process is aimed at targeting the majority of drug takers whose minds are open to being changed. Though, obviously, there are many festivalgoers who are going to consume illicit drugs no matter what, experts on the subject claim that up to 80 per cent of casual drug users can be swayed into making safer choices when armed with more information.

And, in those instances where something of a remarkably dangerous nature is found, the information provided can very easily save a life.

By providing this vital information to the public in a targeted and reasoned approach, the theory is that fewer people will end up taking the drugs, considering how many are revealed to be filled with nasty chemicals. But it’s a common misconception that needs to be emphasized, it’s not necessarily detecting the nasties as to why pill testing is successful in reducing fatalities, but that it reduces overall consumption of drugs through education and therefore it also reduces the risk of someone having an overdose from ecstasy.

And though five visitors to the recent Australian pill testing trial in Canberra discarded their drugs in the bins provided at the testing space, many more, according to those involved, discarded their pills in nearby bins outside the tent too.

Interestingly, of all 86 people treated by first-aid responders at that particular festival, most of whom were treated for drug or alcohol intoxication, none were wearing the armbands given to people who took the safe option and had their pills tested.

There were no deaths, either.

What are some other Benefits of Pill Testing?

- Pill testing has been shown to positively impact the black market drug trade with products publically being identified as dangerous found to leave the market.

- Evidence has found that pill testing can place pressure on manufacturers to refrain from using adulterants or other additives in drugs.

- Pill testing also enables the capture of long-term data on substance usages and the drug market in general. This provides the potential for warning systems against new, unexpected, or dangerous drugs and consumption trends within Australia.

What are some Perceived Negatives of Pill Testing?

- The Government should not be held accountable for the actions of individuals. It’s a pretty simple argument really and makes sense considering that people should know drugs can be harmful. Why should the Government be held responsible for your own decision to put yourself at harm?

- While on-site drug testing is fast and easy, its accuracy can be questionable. The pill testing kits are severely limited in what they actually detect such as contaminants or other toxic compounds.

- On-site test cannot test for concentrations and high doses of ecstasy and methamphetamine are often fatal by themselves as previously stated.

- Pill testing could give users a false sense of security that what they are ingesting is safe or “good”. But again, pill-testing centres always inform potential users that there is no safe way to take illegal drugs.

What’s Next for Australia?

In Australia, pill testing is a concern managed at a state level. Currently, the two major governments digging their heels in the ground about pill testing are New South Wales and Victoria, despite being the two states with the highest body count in terms of drug-related deaths at festivals. Many feel that harsher policing is doing more harm than good, and the NSW government has been particularly dogmatic, presenting festivals with large bills for an increased police presence, including sniffer dogs. By essentially punishing the festivals, people have concerns that it is a ploy to make the format unaffordable and hence, end music festivals altogether.

But there are very strong voices in support of pill testing. Dr Alex Wodak and Dr David Caldicott, both of whom have extensive experience treating the victims of dodgy drugs in emergency wards, have been tireless in their work towards getting Australia on track to implementing pill testing at every festival, in the hope that they will see fewer faces through their respective wards and indeed all emergency wards because of some reasoned action on the ongoing problem.

Though Victorians were late to the party on the hugely successful supervised injecting centres which have seen a huge depletion in the number of heroin-overdoses in NSW, between the convincing arguments on the pro-side, and the people who are voicing them, such as Fiona Patten of the Reason Party, progress does seem to be inevitable.

In Australia, the broader debate centers around the merits of harm minimisation versus a zero tolerance approach to drugs. In terms of pill testing, all evidence seems compelling enough that we can make a breakthrough in terms of legislating and providing for those who aim to actively reduce harm at festivals.

While, for now, politicians are intent on grandstanding to an older generation, many of whom remain unaffected by the lack of support and information for young people who take drugs at festivals, the question of implementing safe and legal pill testing across the board at Australia’s major music festivals would now appear to be less a matter of if, and more a matter of when.

Comments

We love hearing from you. or to leave a comment.