Published:

Readtime: 18 min

Every product is carefully selected by our editors and experts. If you buy from a link, we may earn a commission. Learn more. For more information on how we test products, click here.

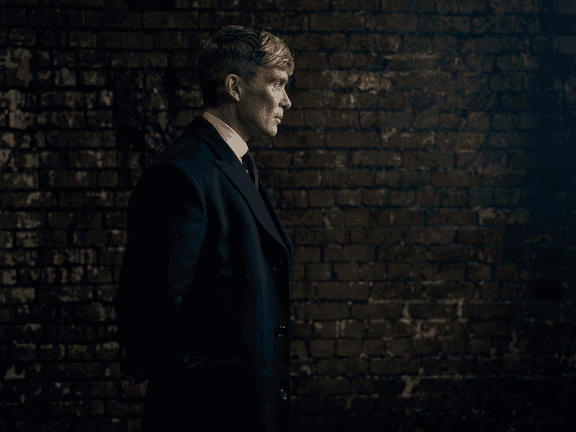

The very first thing shown in Netflix’s hit programme Narcos, even before the title card is revealed to viewers for the first time, is a splash of text across the screen, citing the exact definition of “magical realism” as: “What happens when a highly detailed, realistic setting is invaded by something too strange to believe.”

Though many have mastered the genre–largely Central and South American writers–most will attribute magical realism to the groundbreaking works of Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez. By this definition, magical realism is as native to Colombia as its pioneer, and the notion that it is too strange to believe becomes evident in the two seasons of gripping television which follow.

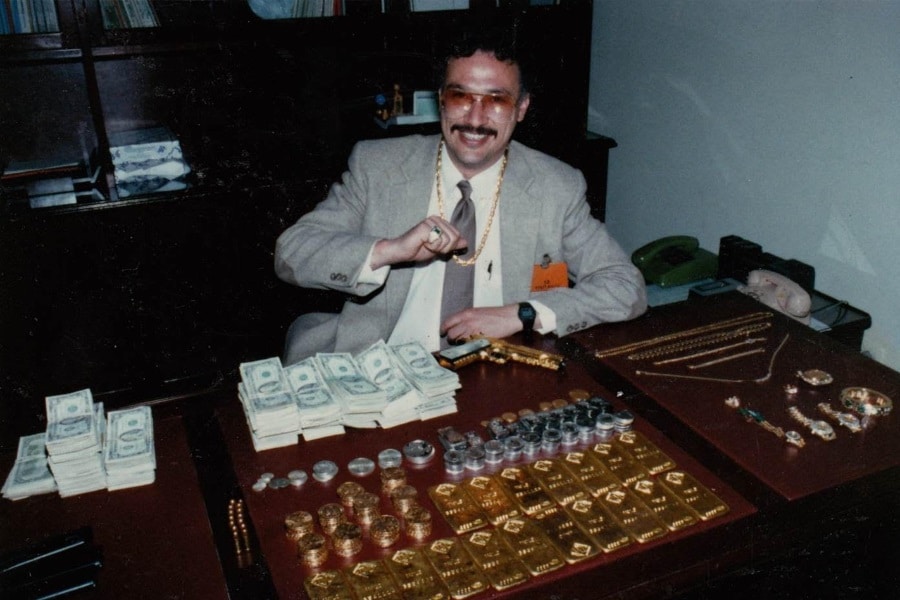

Though many a legend has been told of drug kingpin Pablo Escobar, much of what has been said is either overembellished, or not nearly outlandish enough. Famed equally for his cunning use of charity to win the hearts and minds of Colombia’s poorest as he is for his part in the deaths of thousands upon thousands of people, including Colombian National Police, innocent bystanders, competitors and members of his own Medellín Cartel, Escobar’s notoriety is equally as bemusing as it is entertaining: clearly something the bigwigs at Netflix realised could make for interesting viewing.

From starting what, to some, felt like an unwinnable war, to his famed collection of exotic animals, some of which now allegedly run wild in Colombia, Pablo Escobar became a larger-than-life character before his thirtieth birthday.

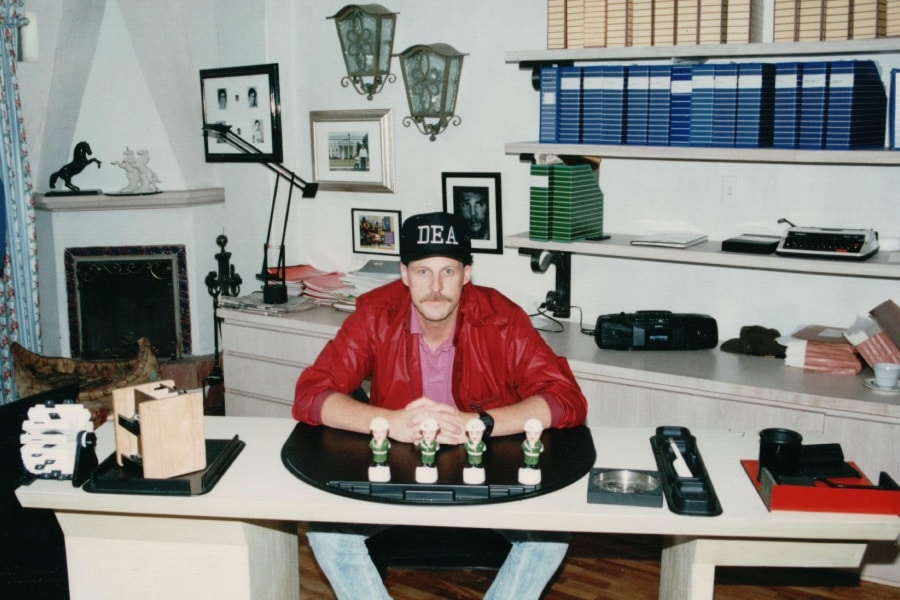

Narcos quickly captured the attention of a global audience for its rawness. Though well scripted, its no-holds-barred approach to showing the rampant violence, sex, drugs and excesses of the Colombian drug cartels was a hit with viewers, and for the first time, offered a holistic look at the lives of those involved; specifically, Javier Peña and Steve Murphy, the DEA agents who risked life and limb on the front line during this war on narcoterrorism.

Played by Pedro Pascal and Boyd Holbrook respectively, the fictionalised versions of Javier and Steve show two highly skilled and dedicated officers of the law, frustrated in their pursuit of the richest criminal of all time, seemingly one step behind the slippery trafficker until the inevitable finale.

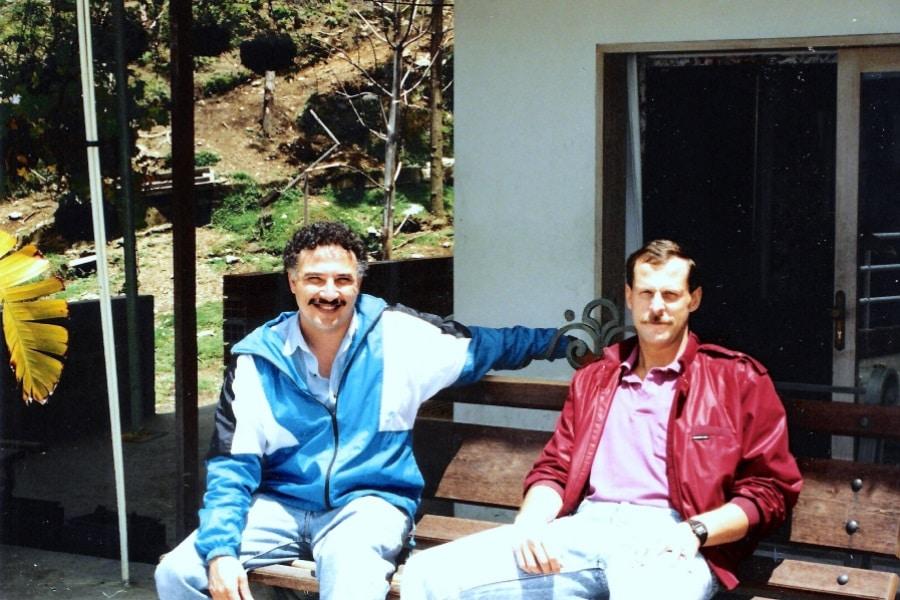

But the real Javier and Steve paint a slightly different picture than that of Hollywood, and have more insight and anecdotes about their years in Colombia than anybody else involved with this lengthy case. Now, in light of Narcos’ immense success, the pair are travelling the world with their live show, giving audiences the most authentic look at Pablo’s crimes, lifestyle and madness to date.

They also shed some light on current drug policy and attitudes, at a time when their home nation is gripped by an opioid addiction epidemic, and as some states grapple with whether or not to legalise certain substances. While politicians bandy drug policy back and forth like a deadly piece of pigskin, these are the opinions of people who have seen friends murdered over a white powder that causes a lot more carnage and needless despair than most people in a nightclub cubicle with a key up their nose probably realise.

Speaking to us from Virginia, and ahead of their upcoming tour of Australia, we were lucky enough to have Javier Peña and Steve Murphy give us their unique views on Narcos, the war on drugs and Colombia’s accidental Hippopotamus problem, seen through their own eyes.

Javier, Steve, thanks for talking to us. I want to know exactly what it was like in the late ’80s and early ’90s, when you landed in a place so far away and so different from your home; especially knowing that your time there wasn’t going to be very easy.

Javier Peña: I got there in 1988 and I had never been out of the US. And I immediately learned that Colombians are … they care very much about their country. We started working with them and I found out they care about their country; they’re very loyal. They’re great people.

With Pablo Escobar, when we started investigating him, we did not know he had that big of an empire–that big of a cartel–and so we formed a unit. We went after him, the police we worked with were first-rate. They were very smart, very dedicated to the Escobar search and we got along very well with them, we helped them out. We didn’t come in there telling them what to do, we were there with them hand in hand and that was one of our basic philosophies, that we were there to help them, and I think that’s what we did and how it worked out.

Did you find it quite easy to live in that place, to get along with the people there or was there some sort of backlash, given that you were foreigners?

Steve Murphy: For me, the only Colombians I had met before going to Colombia–I was stationed in Miami–the only ones I had ever met were the ones that we were putting in jail. You tend to stereotype people, which is not the right thing to do, that’s just human nature, so my wife and I when we got there we weren’t sure what to expect, but we were pleasantly surprised.

Colombians are some of the nicest people in the world. They’re honest, hard-working people. Obviously, you get a very small percentage of drug traffickers that give the whole country a bad name.

As an example, my wife used to go shopping–she had no Spanish training whatsoever. She’d go shopping, she would barter prices, she would negotiate with people. And it would amaze me, I would ask her, “How in the world do you do that, you don’t speak the language?”, and she that said she’d use the few words that she knew, as best she could. She’d have a smile on her face, she had a welcome attitude, she was willing to laugh at herself and as long as you were trying, the Colombian people were very accepting.

Colombians are a very proud people and if you go in thinking you’re going to tell them what to do, they’ll tell you where to get off real quick. If you go in with an attitude of just wanting to get along and respect them and their culture, I haven’t met a nicer group of people anywhere in the world.

It’s an incredible resolve for a people who were going through such turmoil at the time. I want to touch on the hunt for Pablo. You caught him and yet the chase continued for so much longer because of the politics at play. Was there ever a point where you looked at each other and just thought, “Maybe we can’t do this”?

JP: Yeah, you know what, there were times when we just wanted him to surrender and go home because of all the people that were dying off–people he was responsible for killing, the terrorism we saw and there were times, you know … that second search took us eighteen months.

So, yes there were times we were like you know, “I hope he just surrenders, let’s let him”, but then you’d see people get killed, you know, friends, and that would reinvigorate your duty to not give up, to go after him. You know, a lot of people died and we saw the narcoterrorism at its best and a lot of times we just hope he’d surrender and let’s all go home–but when your friends get killed you cannot do it, you gotta keep fighting.

You mentioned seeing people getting killed and I think Narcos, the TV show, definitely gave people more of an insight into what the reality was at the time. And I think Escobar, over the years, has probably been romanticised a bit as a bit of a pop culture icon, and people forget just how much terror he actually caused. Do you think, in hindsight, the TV show has helped raise that awareness?

SM: Well, it’s … a lot of people think–and I agree with you about the pop culture popularity–but one of the agreements we made with Eric Newman, who’s the creator and executive producer of Narcos, from the very beginning, at the end of our very first meeting–and I was concerned that somebody would try to popularise or portray Pablo in a very positive light–and he promised he would never do anything to glamorise Pablo Escobar.

And in our opinion, and we’ve seen all the episodes, we think he lived up to his word.

We’re just as shocked as you are that the show is so popular, but also that younger generation might view him as a hero. There’s this myth out there about him being a Robin Hood, and there is nothing farther from the truth–that’s a big misnomer.

You know, he did build housing for people that didn’t have housing, he built clinics, he built soccer fields, he gave away money, gave away food and those are very good things and that’s where he gained that reputation I guess, but what people don’t know is that when Pablo needed more sicarios, more people to work for him, besides the ones that had been working for him that had been killed in firefights with the Colombian National Police, or the competition, or whatever; where do you think Pablo went to get his new recruits?

Right back to those barrios where he’d give them housing, because they thought he was a God, you know. And the sad thing is, he might go in there and ask for a hundred people to volunteer to work for Pablo Escobar and you might have four hundred that would step up and want to do that. So what we’d say is he’s not a Robin Hood, he’s a master manipulator, because he manipulated his people.

The ‘war on drugs’ is what it’s been called for a long time. In hindsight, a lot of people think it’s a success and a lot of people think it’s a failure depending on which side of the political fence you’re on. But it does feel like the mythical beast Hydra, where you cut off one head and two more grow. Once Pablo was finished, more cartels cropped up, cocaine use, opiates, methamphetamines all over the world are rampant–especially opiates in America right now. You guys are very experienced and highly celebrated. You’ve risked your lives on the front line to save innocent lives. Do you think that maybe its time the narrative changed from ‘drugs are bad’ to something a bit more realistic, and less simplistic?

JP: Yes, I think so. And you hit it right on the head when you say the cartels–if you look at the history in Colombia–when the Medellín cartel went down in Columbia what happened? The Cali cartel took over. The Cali cartel got wiped out, then now you look at the situation in Mexico, where there’s all these cartels… You still need the enforcement, you still need to go after these traffickers because some of them think they’re invincible.

You look at Chapo who’s on trial right now in New York City. We need to get better at the educational level at the society level, at the responsibility of people. It’s got to be a well-balanced approach where you have, like you said, you have a lot of demand in the United States for drugs, you have a lot of users, we have a lot of problems: addiction rate, people dying, the problems are caused by drug addiction. So, you have to continue–there are still drugs out there–but where you need to get better is in the educational process.

With drug abuse, the end game really is a supply and demand question. Do you think addicts, or people who use drugs, should be considered criminals, or do you think they should be considered patients?

SM: Wow, that’s a good question; a hard question.

Because, I guess my point is if you take away the supply from being criminal to being able to regulate it, tax it–like they’re doing with cannabis, for example, in Colorado and California, do you, in essence, take the power away from the criminals when you do that?

SM: Well, alcohol is legalised in every country around the world, just about, and do you still have moonshiners? Yes, you do. Even here in the United States.

Marijuana is legal in Colorado but you know one of the biggest black markets where illegal marijuana is? Colorado. The Mexicans bring it up there because they can blend it in so well and they sell it cheaper than what the legalised marijuana is. The argument about legalising drugs, first of all, if you’re legalising just for taxation, I think that’s completely wrong. Somebody’s health, and the safety of the public? You can’t put a dollar amount on that, I don’t think, for something like this.

The other thing is, there are so many unintended consequences that go along with the legalisation of any narcotic, whether you’re talking about marijuana or cocaine, meth, whatever it might be–opioids, that whole thing–so if you legalise it, we’re encouraging people more or less to try the drugs, because they’re legal.

It’s just like when we were kids, one of the kids would sneak a beer out of dad’s refrigerator and we’d all take a drink of beer, next it was wine, next it was hard liquor. What do we do with all these people when they become addicts and they can no longer take care of themselves? Should you and I be responsible for taking care of them because we’re straight and we have jobs and we pay taxes? I don’t want to be responsible for those people. They made their own decision, they have to live with the consequences.

Javier, do you have an opinion on that?

JP: Yeah, I agree with Steve. It’s a hard situation and with all the addiction, what we’re seeing now, and you know, also, a lot of times we know that the trafficker doesn’t touch the drugs, he’s the one who’s controlling it, he’s the one setting his own empire. He may not be in this country, a lot of them are in other countries and they have the wealth of the world, so why are these people getting rich off the misery of other people? And it’s just … like I said, it’s a problem.

We used to have a programme called DARE in schools. A lot of people went through it, we talked to people, school kids were going through it and the funding was cut and it went away. Some rich districts, school districts, had money to maintain it but a lot of school districts did not, so again, we need to get better with our societal responsibilities and when I’m talking societal responsibilities I’m talking about everyone – families, religion, friends, teachers, whoever is out there that can help out–we need to start at an earlier age and we need more of a balanced attack.

I appreciate you both answering that honestly. Steve, you were there on the rooftop on the day Escobar got taken out. And I’ve heard it’s a secret location, mainly because Colombia doesn’t want to make a hero out of him and doesn’t want to make a tourist attraction out of that rooftop. Have you been back there and has it changed?

SM: Well, first of all, I was not on the roof – that’s a Hollywood thing.

That operation that day that killed Pablo was nothing more than Colombian National Police out there, so if you read that book “Killing Pablo”, I think is the name of it – they would lead you to believe that there was an American sniper out there.

I wasn’t there, but we have been back. Javier and I were there, well Javier was there before they started filming season one of Narcos and then we were both there March of last year, about a year and a half ago, to film another show called “Finding Escobar’s Millions”.

And do you find there’s any big difference there–has the area changed a lot? Obviously, at the time it was pretty much his place, and other parts of Colombia had very different opinions of him. Is there any hangover left over from the era when Pablo ruled the roost?

JP: Like Steve said, I went back with the Netflix people, who wanted to see where everything was; where he lived and the places where he slept … and I was disappointed. They had torn down the area we used to stay at. To me it was part of history.

Then we went to the prison and, wow–they turned it into a monastery. Like you said, I’m not sure if they wanted to get rid of the negative connotations that were sometimes involved with this, whether it be true or false. I think the only thing they pretty much kept is the ranch, but that has changed too.

But as far as Colombia right now, it’s a great country, we encourage people to visit. It’s safe, we tell people, the police in Colombia–it’s a model police , they’ve changed one hundred per cent, it’s safe.

After every show we encourage people to go visit–it’s just great people, a beautiful country and if you go online you’ll see there are Escobar tours, Escobar tourism and I hear that a lot of people are taking the Narcos tour.

You mentioned the tour you guys are doing as well, I wanted to ask you a bit about that, because Narcos is huge in Australia. What can people expect when they come to see you live?

SM: You know this is our second tour over there, we were there a couple years ago in Sydney and Melbourne, we sold out the Sydney Opera House believe it or not, which were tickled to death about, and in Melbourne we even sold out Hamer Hall, so this time we’re coming back to Sydney and Melbourne, plus Brisbane, Perth, Hobart and Canberra.

What people can expect to see and hear is the truth. And that’s what we do, we get up and tell the true story of Pablo Escobar and what really happened. Don’t get us wrong, we love the show Narcos, it’s one of the best action series that I’ve seen in a long time. I think Javier would say the same thing. We’re very happy with the actors that portrayed us and how they portrayed us, but we’re going to take people on an adventure.

We’ll tell them how Pablo got to the position he was in, take them inside of a cocaine lab so they can see how cocaine is made, what it looks like inside of a lab. We’ll show them a little about what Pablo did with his money, take them inside his famous ranch.

We talk about what we call the deal of a lifetime, the deal he negotiated with his own country. He surrendered at his own custom built prison, then we take them on a tour through the prison. We talk about Los Pepes, believe it or not, so we tell the true story about that.

And then, at the end, we have a reenactment video so that they can see for themselves what really took place that day that Pablo was killed, and it’s told by the Colombian police officer that found Pablo Escobar that day. It’s very authentic.

At the end of every show we always have a question and answer session. They can ask us any questions. They can ask about Narcos, the investigation, any of the other programmes we’ve been interviewed for. It’s not a lecture, we try to get people to laugh, try to get the audience involved, we want everybody to have fun, have a good time–it’s not like anything they’ve ever seen before.

JP: And it’s part of history. We’re actually telling people the real history of the rise and fall of the Medellín cartel.

I want to finish on something a little bit of levity because I know there is a funny side to this, which I think is the hippopotamuses which now roam the streets of Colombia. Whether that’s myth or not, you guys have been there, you can probably tell me a bit about the fallout from Pablo’s ridiculous collection of exotic animals?

SM: What the hell! I’m not sure what happened. Do you know Javier?

JP: Yeah, I know some animals were taken to some zoos, not sure where. Obviously we know about the hippos that escaped and now have their own herd of hippos roaming around Colombia. He had all sorts of animals, I understand some were moved to zoos, hippos had escaped and started their own herd.

And the ranch is still there, I know people visited, and that he had a play park with giant-sized dinosaurs. [There’s] all sorts of stuff that’s being used as a tourist attraction.

But the hippos … they’re destroying a lot of crops.

Javier Peña and Steve Murphy are touring Australia from 19th-29th of July 2019. Tickets are selling fast, and are available via the link below.

Get Tickets to A Conversation on Narcos With Steve Murphy & Javier Peña Here

Comments

We love hearing from you. or to leave a comment.