Seventy years ago, visionary winemaker Max Schubert’s homage to Bordeaux left critics divided. Now, it’s Australia’s most coveted release.

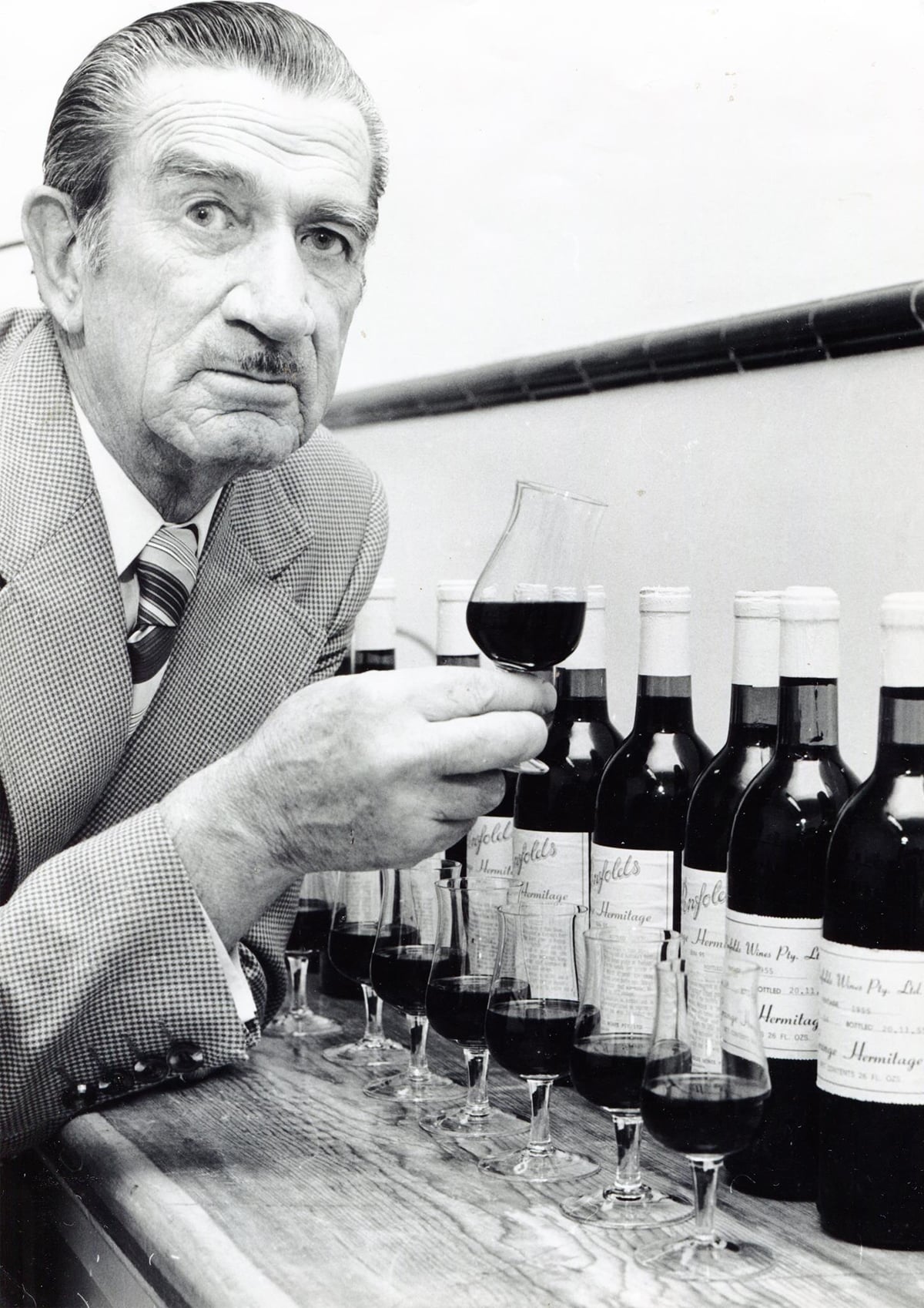

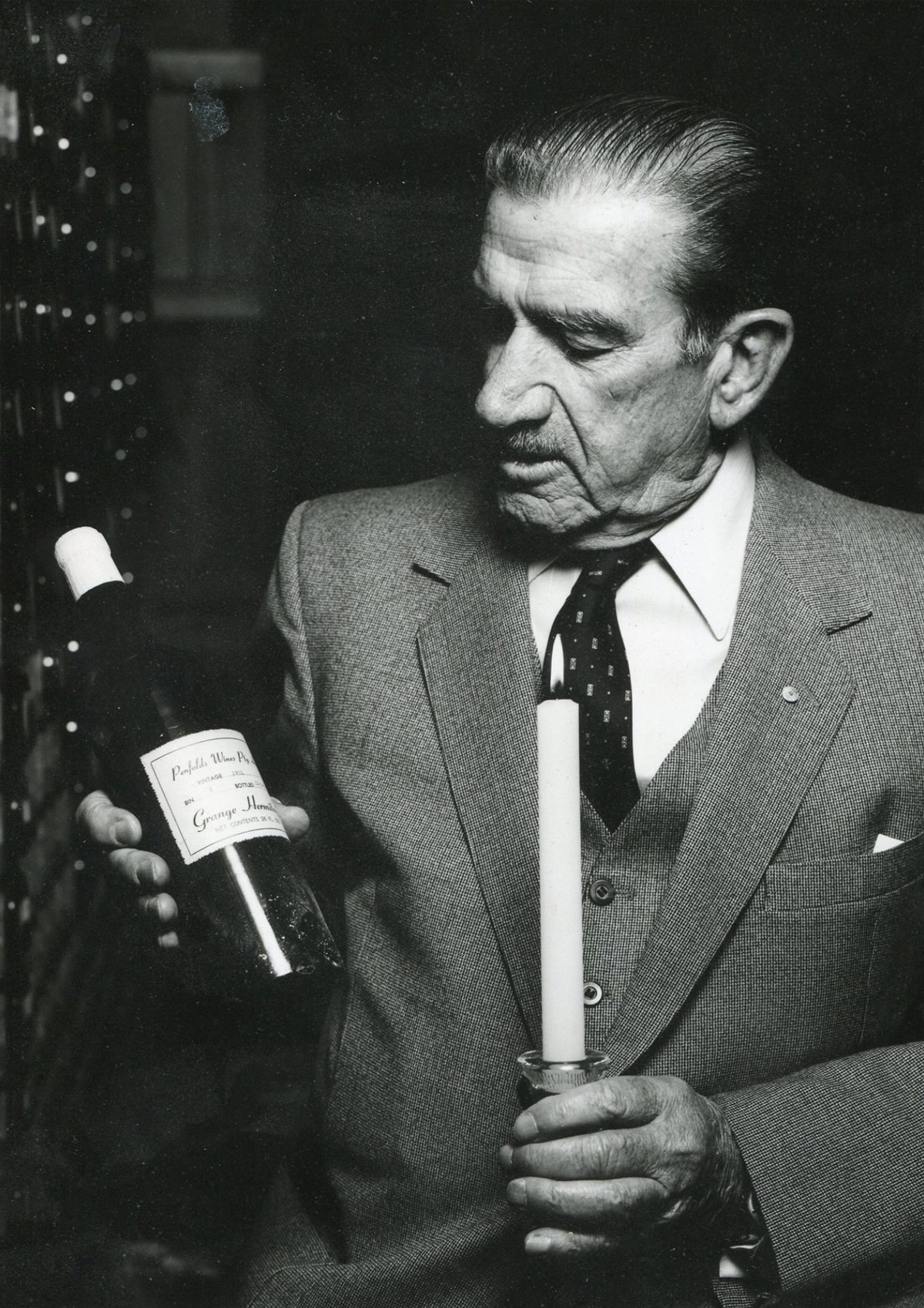

At the midway point of the 20th century, Australian winemaking hit an unexpected apex. The cottage industry, which up until that point had largely been a fixture of fortified production, was thrust head-first into the modern era by a decadent, fruit-forward shiraz that defied all convention. Emerging from Penfolds’ Magill Estate cellars with an experimental bottle of Grange Hermitage Bin 1 tucked neatly under his arm, visionary winemaker Max Schubert believed wholeheartedly that he was about to put South Australia on the map. Critics disagreed.

Wine writers dismissed it outright, the Penfolds board rejected it, and Schubert was politely yet firmly asked to cease production. Seventy-four years later, Schubert’s vision came full circle, when a single bottle of that very same vintage went under the hammer for the staggering sum of AUD$150,000, making it the most expensive bottle of Australian wine ever sold at auction. Not bad for a drop once described as having tasting notes of ‘crushed ants’.

The Grange Gamble

The story of Grange is one of driving clarity of vision. When Schubert first conceived the award-winning wine, he wasn’t thinking about playing by the rules. Inspired by his journeys abroad, the winemaker envisioned an Australian release with the structure and longevity of the great Bordeaux reds. Seeking something bold and experimental that was ‘capable of staying alive for a minimum of twenty years’, Schubert landed on a unique blend that he believed had the potential to disrupt the entire industry. As spiritual successor and current Penfolds chief winemaker Peter Gago explains, Schubert was ahead of his time, in more ways than one.

“It was a provocative in-your-face change of tact all those years ago when Max went to Bordeaux—it was cutting-edge at the time,” Gago tells me. “We were already using small oak in Australia, but he put a lot of these things together and created this wine called Grange, which was misunderstood in its early days and was very different.”

As Gago explains, Schubert’s first experimental vintage was unlike anything Australia had seen before. Rich, full-bodied and aged in American oak, the inaugural 1951 release laid the foundations for what would eventually lead to a signature wine style, but it failed to hit the mark initally. The problem, according to Gago, wasn’t the wine itself—but rather, the timing.

“My theory is that Max was so excited about it that he probably poured it and showed it to people too early,” he tells me. “It was raw, it was unevolved. Now, we don’t release Grange until it’s four or five years old. But back then, it was this full-throttle bold, raw wine being poured for people, and it was misunderstood.”

Uncorking a Signature Style

After production was halted by the Penfolds board, Schubert famously continued to craft his Grange vintages in secret, hiding three vintages in ’57, ’58 and ’59. The decision proved invaluable and in the decades since, the sentiment around the wine has shifted dramatically. In the early 1960s, the unique blend steadily gathered steam on a domestic level and by the middle of the decade, Grange had achieved international recognition. Remarkably, the formula has remained almost entirely untouched.

“Grange is a traditional style. We’ve never changed the stylistic template,” Gago explains. “We’ve refined it but never changed the style. Why? Because it isn’t broken. We don’t have to continually change things. With Grange, it even defies every marketing axiom. There’s too much writing, it’s monochromatic, it’s the world’s worst wine label, but we’re never going to change it. Those ironies, those idiosyncrasies are just so compelling when it comes to this thing called Grange.”

In the grand scheme of luxury winemaking, the Grange process is delightfully A-typical. Where other prestige releases are tied to a specific vineyard or region, Grange employs a strictly multi-regional approach.

“Because it’s a blend, we can do that,” Gago says. “It might be a bit too warm in the Clare Valley, but it’s a great year in Coonawarra. It might be mediocre in the Barossa, but ‘Oh gee, down in Wrattonbully, things are looking good.’ So we have that dexterity.”

Blending By Necessity

The agile approach wasn’t always seen as a positive, but rather a means to production. When Max Schubert worked on his initial Grange vintages, he was hampered by limitations to the cellar equipment and available grape yield. The use of Quercus alba American Oak, for instance, was simply because there wasn’t much French oak on offer. Similarly, Schubert’s decision to use Shiraz as a grape varietal base came out of necessity, with “so little A-grade cabernet in Australia” available at the time.

“This became a very brave new blend, but it was still sort of conically what it had to be because of what he had available. It almost had to be Shiraz,” Gago says. “The cellar at Magill made the style of Grange as a consequence of what was left from the 1800s; open fermenters, a basket press, and channels leading into runoff tanks so the wine was wrapped in return daily because that’s what that cellar could do. It was a consequence of the dynamic of the cellar in a mechanistic way, coupled with what he had available.”

As Gago reveals, flexibility has become the defining characteristic of the flagship release. Drawing from different regions allows the Penfolds winemaking team to maintain consistency, even in challenging vintages. You could also chalk this up to the winemaker’s ‘blind tasting’ classification process, which has been in operation for well over 60 years.

“You simply make a selection purely on sight, smell and taste, all of which drive the quality and the style,” Gago says. “Only when you put the blend together later do you find out the percentage of the cabinet. That’s why the volume varies annually.”

That’s not to say Grange is a guaranteed yearly release, however. Gago jokes that 2000, the millennium year, would have been a perfect time to drop a special release Grange vintage, but the environment had other ideas.

“It was a difficult year in South Australia. It was a great year in Bordeaux, a great year for vintage port, but not so good here in South Australia,” he explains. “We made less than one-quarter of the average volume of Grange in that year and perhaps that’s why the board still hate me to this day, but volume is not deliberate.”

“Some people may suggest that we’re deliberately making less Grange to drive rarity and get the price up. And I say to that, we’re not that clever.”

The Penfolds chief winemaker may be coy and disarmingly self-effacing, but Gago sits, quite literally, alongside some of the legends of Australian viticulture. When we chat, he is holed in a rather dimly-lit room, which he jokingly acknowledges looks not unlike a ‘prison cell’, but like many things at Penfolds’ Magill Estate, looks can be deceiving.

The chief winemaker, flanked by images of his predecessors, sits in the very same room that once belonged to Jeffrey Penfold Hyland, son of founder Dr. Christopher Rawson Penfold, and even more remarkably, Max Schubert himself.

Icons of Style and Spirit

Since joining Penfolds in 1989, Gago has overseen an incredible run of Grange vintages. As head of the winemaking division, the Aussie icon has signed off on the last 23 releases, each time aiming to capture some of that initial Schubert magic.

“With Penfolds…you have the best of the history and the tradition. What I try to do with the team every year is make a wine better than the ’52 and the ’53. That’s the objective,” Gago says. “We’re just about to enter year one of our next 180 years and to be part of that, certainly for the last 35 years, has been a great thing and something I’ve not regretted. The world of wine is quite real, quite palpable and quite sexy for a lot of people. The sexiness wears off very quickly. It’s got to be real.”

“When things are real, you don’t have to remember, it just sort of happens. And it’s been pretty real ever since.“

The Price of Perfection

A far cry from the initial rejection of the 1950s, Penfolds Grange is undeniably Australia’s most important wine. The flagship release from the country’s most revered winemaker has enjoyed an incredible rise in popularity, reputation and, most significantly, price. The 2010 and 2018 vintages, both of which Gago notes as career highlights, were met with perfect 100-point scores from numerous wine writers across the globe. These releases not only underscore the quality of Grange but also its importance to the wider Australian wine landscape.

“Grange is one of the most serious wines on planet Earth in terms of its longevity and its propensity to age,” Gago says. “As Australians, we love to back winners. When Grange gets perfect scores, everyone wins. The tide rises for Australia, and this is the great beacon globally.”

Importantly, Grange’s success has reopened the doors for experimentation. Just as Schubert aimed to break the mould with his inaugural vintage, Gago and the Penfolds winemaking team are experimenting with techniques, albeit not on the flagship release, to craft new and enticing wines.

“Grange is what gives us the license to make other things,” Gago says. “In the ’90s, that led to RWT. Some people thought Grange was a bit old-fashioned with its American oak and blended properties, so we said, ‘Well, here’s RWT.’ It’s in French oak and it’s single-region only Barossa Valley liquid. So we leave Grange alone and create a contemporary alternative. We have that base, that foundation, and Grange gives us the authenticity, the credibility, and the license.”

The Future of an Icon

For Penfolds, now more than 70 years into its Grange journey, success is driven by heritage, but Gago admits that the future of the flagship blend is rooted in innovation. Over the past few years, the South Australian winemaker has invested heavily in its vineyards, implementing a series of sustainability and regeneration projects. This, coupled with the influence of grower liaison officers who act as internal consultants for growers, is helping to drive long-term success and ensure the longevity of Australia’s most significant wine.

“The future is as important as the past,” Gago says. “Part of the Grange story is the many, many different components adding to the complexities. We’re not just painting in black and white. There are many, many vivid colours added into the mix.”

Gago’s analogy is delightfully apt. Like so many artists that have come before, Schubert’s first showing may have faced criticism for being underdone and a little out of left field, but it didn’t quash his enthusiasm. What started as a nod to Bordeaux boldness transformed into a national icon, with each bottle carrying Schubert’s vision in its DNA. If you ask Gago, Grange is not simply a flagship Shiraz with a touch of Cabernet thrown in; it’s an ode to Australian terroir.

“We are only the custodians of it,” Gago says. “I may sign off on it as Chief Winemaker, but this thing belongs to Australia, it belongs to Penfolds.”

First unveiled in 1951, Penfold Grange remains one of Australia’s most significant wine collections. Made from predominantly Shiraz grapes and a small percentage of Cabernet Sauvignon, the blended drop is widely considered one of Australia’s “first growth” and its most collectable wine. On the 50th anniversary of its launch, Grange was listed as a South Australian heritage icon.

Comments

We love hearing from you. or to leave a comment.