Blancpain, Biopixel & the Battle to Save the Great Barrier Reef

Published:

Readtime: 8 min

Every product is carefully selected by our editors and experts. If you buy from a link, we may earn a commission. Learn more. For more information on how we test products, click here.

When swimming in deep water, there are any number of things you don’t want to experience, but somewhere near the top of the list must surely be a sudden, unshakable sense that you’re being watched. During a recent visit to the Great Barrier Reef with Blancpain, a marine researcher described this sensation to me as “feeling sharkie” and insisted it’s something you ignore at your peril.

You’ll also love:

Blancpain’s Fifty Fathoms Scores Titanium Upgrade

A few hours after that particular exchange, I found myself floating about 50 metres from the boat that had been puttering us around to various dive spots throughout the day. Looking down into the inky depths, I suddenly felt the “sharkie” sensation shoot through my veins like ice. While trying my very best to appear unflustered on the surface, I kicked my way back to the boat and was out of the water in a flash. Later that evening, I described the feeling to another reef expert, before reassuring myself out loud that it was all in my head. His response: “There’s no guarantee.”

He was all too right. In fact, it seems there’s very little that’s guaranteed when it comes to the Great Barrier Reef, including its chances of remaining “great” for much longer without dedicated action to ensure its longevity. Much to the surprise of myself and the other guests present for our aquatic jaunt, Blancpain didn’t invite us along in order to reveal a fancy new dive watch – despite being the brand that developed the world’s first modern dive watch and has a CEO known for his diving enthusiasm – but rather to press upon us the importance of reef restoration and preservation. This is a cause Blancpain is helping to drive through a partnership with a charmingly ragtag but absolutely devoted and highly skilled outfit called Biopixel, which operates alongside a handful of affiliate organisations and volunteers.

An Emmy Called “That Old Thing”

To put it simply, Biopixel is the Emmy Award-winning team of marine biologists and underwater cinematographers that David Attenborough hits up when he needs some slick footage of the Great Barrier Reef for his next documentary. But not only does Biopixel immortalise the natural beauty of the underwater world for us to enjoy from the comfort of our living rooms, the team’s heavily involved in a range of projects designed to protect and restore the Reef for generations to come.

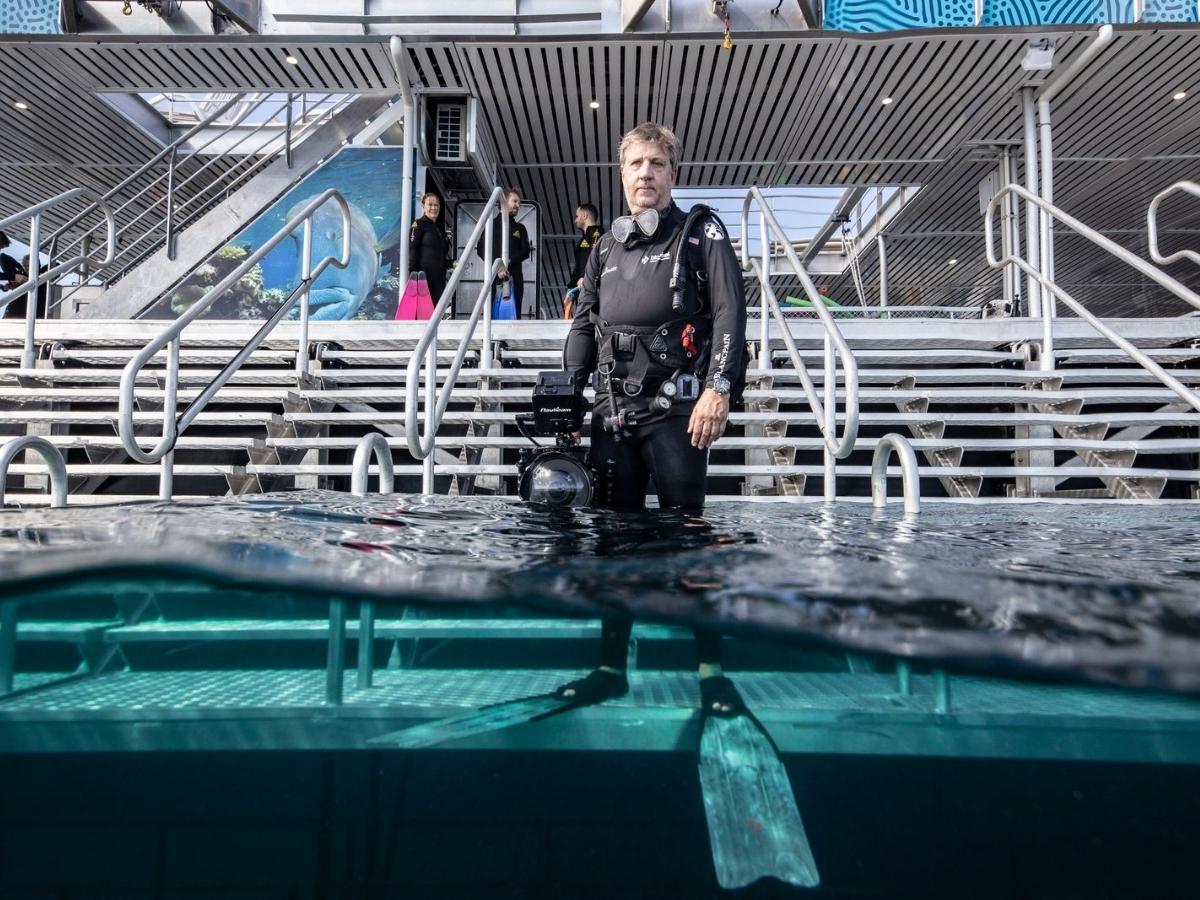

Operating out of James Cook University, Biopixel is led by Richard Fitzpatrick, a man who’s had more one-on-one time with large, carnivorous marine life than any sane person should admit – and yes, Fitzpatrick refers to the team’s Emmy as “That old thing.” He established the underwater photography side of Biopixel in 2013 alongside Bevan Slattery and a few years later the pair expanded into conservation with the Biopixel Oceans Foundation, which is dedicated to research, exploration and education.

During our brief but inspiring time with this team of remarkable individuals, we saw a number of projects that gave us hope for the future of the Great Barrier Reef and the mission to protect and restore underwater life more broadly.

The Professor & His Fish

First, we met Professor Jamie Seymour of James Cook University. He’s the director of the Tropical Australian Venom Research Unit and a man whose enthusiasm for odd and deadly sea life is infectious, from the tiny but incredibly dangerous jellyfish he keeps in a tank to the venomous stonefish he’ll casually cradle in his hands. With his team, Seymour explores the potentially enormous medicinal value of these creatures, whether by using box jellyfish venom to overcome pancreatic cancer or taking the fight to bacteria that’s resistant to antibiotics.

Seymour’s also known for his collaboration with Fitzpatrick on Biopixel’s Aquarium Studio, one of the largest dedicated marine filming facilities in the world. Here, the Biopixel team is able to capture aquatic events that would be impossible to film in the wild. So the next time you hear Attenborough narrate that a scene “has never before been captured on film”, it could well have been shot using controlled conditions under Seymour’s supervision.

Sitting alongside some of the filming pools, Seymour’s research facility also boasts an offshoot of the Cairns Turtle Rehabilitation Centre – more on that a little later – with the filming facility surrounded by tanks that contain a number of turtles at various stages of their journey towards being returned to the wild. As an aside, it was here that attendees discovered turtles actually like to have their shells scratched, much like a puppy would its back. They’ll splash their fins in approval and swim back around for another scratch.

Reef Restoration

When it comes to actually protecting the Great Barrier Reef more directly, there are a number of ways in which the Biopixel team and its affiliates are making a tangible difference. The first is through the Mars Assisted Reef Restoration System (MARRS). Yes, that’s Mars as in the chocolate company, which has recognised that 90 per cent of the world’s coral reefs could be gone by 2050, having a devastating effect on biodiversity and populations worldwide.

In order to address this, the team developed a process that’s been successfully deployed both here in Australia and for numerous other reefs worldwide. This process includes fixing a number of hexagonal metal structures (known as Reef Stars) into parts of reef that have been bleached beyond repair. These Reef Stars – 348 of which have now been deployed – are coated with resin and coral sand, which are designed to encourage corals and other animals to settle, helping to rebuild the Reef.

I saw the extraordinary results of this program for myself. Visiting four different locations that had received the MARRS treatment over the last 18 months, the effectiveness of the strategy was clear. While the newest installation looked like little more than a collection of metal frames, as we visited each new location the progress was clear. When we finally arrived at the oldest installation, it just looked more or less like a healthy, functioning reef. It was truly impressive.

Rise of the Machines

Another system being deployed to help the Great Barrier Reef return to its full glory is the deployment of robots designed to either eliminate destructive Crown-Of-Thorns Starfish (COTS) or disperse larvae to help the Reef regrow. Operated out of the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) and overseen by robotics expert Professor Matthew Dunbabin, these drones are having a dramatic impact on the health of the Reef.

The program uses two different but equally important robots. The first is the “COTSbot” (Crown-Of-Thorns Starfish robot), which helps to control the starfish population by delivering lethal injections to individual organisms before human divers sweep in to remove any survivors. The second, “LarvaBots”, took over the responsibility for larva dispersal from human divers and have proved themselves capable of deploying more than 10 times the amount of coral larvae into depleted areas of the Reef than their fleshy predecessors.

The program has been extremely successful, with Dunbabin informing us it has seen a 100 per cent success rate in delivering coral larvae to damaged reefs and 99.4 per cent accuracy in detecting COTS.

Heroes of the Half-Shelled

Finally, we can return to the aforementioned Cairns Turtle Rehabilitation Centre. On our last day with the Biopixel team, we were treated to a guided tour of an impressive not-for-profit facility operating behind the curtain at the Cairns Aquarium. Here, sea turtles of the Green, Loggerhead and Hawksbill varieties – to name but a few – are cared for until they’re ready to dive back into the big blue.

From boat collisions to limb damage, infectious diseases to the trauma that comes with net entanglement, many of the turtles we saw had been dealt a bad hand, but the dedicated team led by Jennie Gilbert does great work treating their shelled patients, with over 170 having been helped by the organisation.

There’s a Big Ocean Out There

The efforts of Biopixel and its affiliates go far beyond even the ambitious projects I’ve outlined here. I haven’t touched on the Megamouth project, which tracks whale sharks and manta rays, or the Raine Island project, which sees the team attempting to address turtle reproductive challenges.

The scale and breadth of Biopixel’s efforts are truly remarkable and I’m grateful the team is out there doing all it can, with the support of Blancpain, to ensure that the Great Barrier Reef and the awe-inspiring creatures that inhabit it are in with a shot of enduring for the centuries to come. Even if that means future generations must in turn endure the sensation that comes with that “sharkie” feeling.

Related: Discover more about the Blancpain watch I was able to wear while diving.

Comments

We love hearing from you. or to leave a comment.