I’m sure you’ve read the headlines by now. The social media platform formerly known as Twitter has seen millions of users vanish, and amid the mindless barrage of paid promotion, hate speech and influencer culture, an increasing number of digital refugees are seeking sanctuary in Bluesky: an open-source alternative that has seen its user count grow by 1.5 million in the past few weeks, and which people are comparing fondly to a time before algorithms ruled our lives.

But Bluesky is far from the only alternative out there, and people are definitely not only leaving X.

I recently deleted TikTok off my phone for about three weeks. In the lead up to the U.S. election I was almost exclusively being served content that was bashing Republicans and cheering on the Democratic party, which I readily consumed, but when the votes started being counted, and I saw what was going to happen, I pre-emptively deleted the app.

I didn’t want to see the left-leaning side of TikTok mourn that loss, and now a few weeks after my social media detox, I can say it was the right call. However, after returning to TikTok this week and already having lost a few hours to mindless scrolling, I have to wonder what I’m really getting from it.

A lot of ads, and a lot of people talking at me, that’s for sure.

For the past three years, most major social networks have noted diminishing returns. Facebook’s user growth stalled in 2022, largely thanks to its failure to court Gen Z. It’s increasingly seen by young people as out-of-date, and largely as an advertising platform more than a means to connect with actual people.

RMIT’s Professor George Buchanan, who has spent the past two decades researching the internet and social media, tells me it’s pretty common for a new generation to eschew what older generations have done in order to cement their own identity.

“Facebook eclipsed MySpace pretty quickly, and then we had a Twitter generation of what we called micro-blogging,” Buchanan said.

Twitter, now known as X, wasn’t as popular as its Meta-owned rival even before Musk purchased it, and it has only polarised its users and advertisers more as he exerts more control. I’m not in Gen Z, but I haven’t used Facebook or X in years.

That’s not to say Meta’s other platforms are struggling, by any means. Instagram is doing fine (though with increased competition from TikTok), Threads is growing solely, if consistently, and its messaging apps, Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp, are both used by millions of people every day.

However, we’re increasingly seeing people splintering off into new and different social media than the ‘legacy’ platforms.

If people are leaving these platforms, or are simply not signing up in the first place, where are they going instead?

Human connection? There’s an App for That

The shift in user consumption fundamentally falls back to one question; ‘What do people actually want from social media?’. The initial goal seemed to be to connect people with friends and family, as well as share interests and memories. Now, it seems as though social media’s more pressing objective is to be everything to everyone, at all times, endlessly. It’s a direction that not only poses a moral conundrum, but has, I would argue, led to a worse user experience, if not a worse business.

It’s difficult to imagine another social platform gaining the same kind of foothold as Meta did in the mid-2010s, but there are signs of disruption. A steady stream of boutique networks launched in the past few years are rapidly gaining their own audience—built on the premise of actually fostering genuine connection between people.

For example: NoPlace, a once invite-only app that seeks to take social media back to the early days of MySpace, with all the page customisation, close friends lists, and the drama that those lists created (and which its Gen-Z creators never actually lived through). It’s now available to anyone, and spent time at #1 on the iOS app store when it first launched.

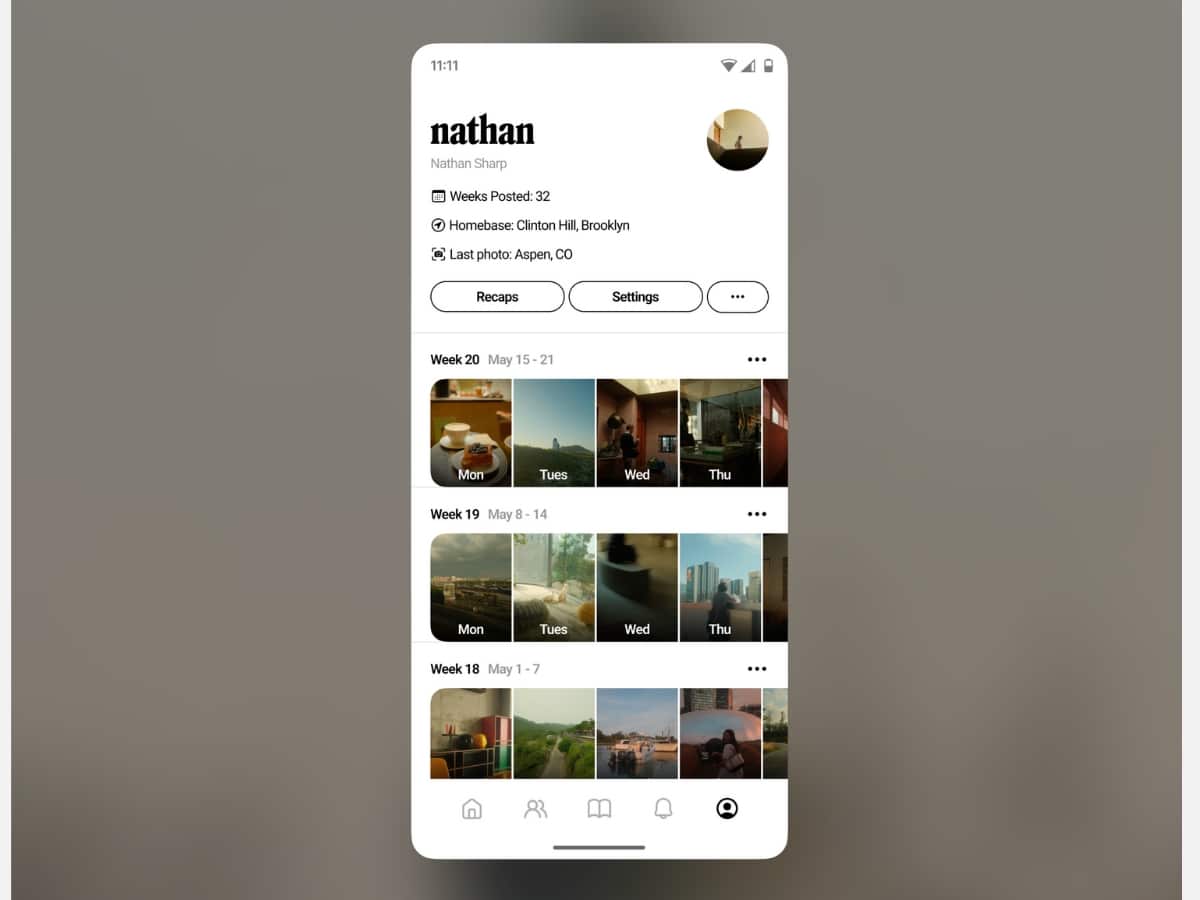

Retro, a photo-sharing platform built by former Instagram employees, is also seeking to change the way its audience interacts with photography apps: narrowing the focus back onto sharing content with people you actually know, rather than broadly publishing it to anyone that’s also using the app. If that sounds familiar, you’d be right.

Retro is the brainchild of two former Meta employees, Nathan Sharp and Ryan Olsen, who were responsible for bringing some of Instagram’s most memorable features to life. A digital idealist, Sharp explains that even during his tenure at Meta, he could see the value in keeping social networks smaller.

“When we look back on , our favourite time was actually the month before we launched it publicly, when it was only our friends and co-workers,” Sharp explains.

“At the time, Instagram had become a place where you just shared your occasional highlights, and there were some co-workers that we were best friends with, but we had no idea what their life was like outside of work, but when they’d get access to the pre-release feature you’d start seeing little windows into their lives. We were always really fascinated by that.”

There’s a part of Sharp that bemoans the fact Instagram’s Stories became another way to ‘build an audience’, rather than a place to share updates with close friends and family. It was this frustration with the direction most social media was heading in that eventually led to the founding of Retro, he reveals.

“Every single one of the social products that used to serve the connection-among-friends use case has gone super deep on the entertainment-from-creators use case,” he says.

“And if you’re platforming content with the intent to entertain, it crowds out the content from your family and friends.”

As with many other smaller-scale platforms, Retro encourages users to keep their circle modest to enable more intimate connection: sharing a quick picture of how good your morning coffee looks might be a bit weird to share to an open platform, but it’s not so strange when you know the 10 other people that’ll see it.

In fact, that smaller user base is exactly what allows people to be more free in what they post to the app, Sharp argues, comparing how people use social media to how they’d use a dance floor. If you’re surrounded by dozens of strangers in a busy club, you’re probably going to feel self conscious about how you present yourself, while others might be performative, but if you’re hanging out with your friends, dancing away in your loungeroom where no one but people you trust can see you, you can be yourself without fearing ridicule.

For now, Retro is entirely ad-free, and is instead moving toward an optional subscription offer with added benefits to support its development moving forward (in a similar way to other apps, like Tinder and Hinge, do).

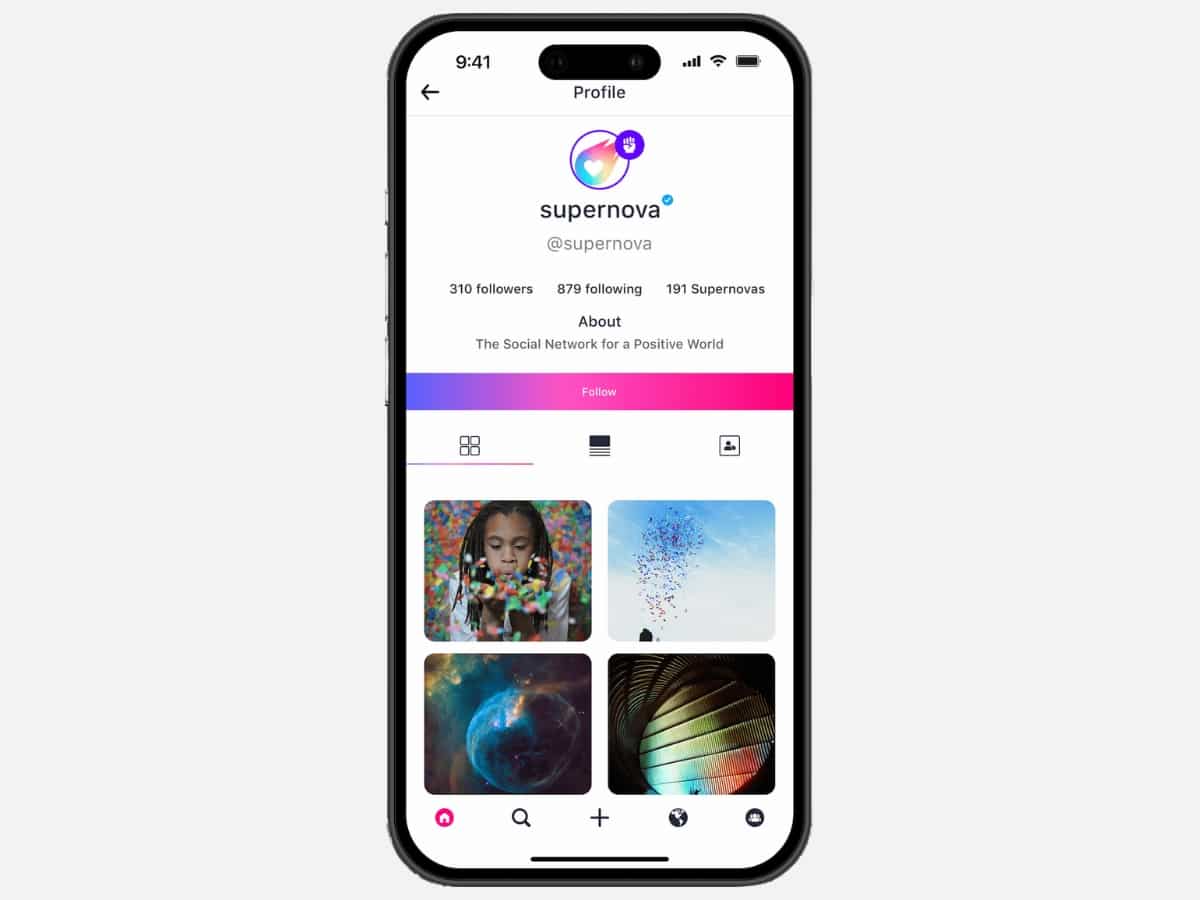

On the other hand, UK-based Supernova does display ads, but each month donates a percentage of all ad revenue to a number of transparently shared charities, ranging from tackling climate change, to food security, to homelessness.

The goal, Supernova’s founder Dominic O’Meara tells me, is to make a social media that actively gives back.

“Fundamentally, it struck me that it wasn’t really fair for the social networks to hold onto all the advertising revenue when the content that got people looking at it was made by users,” O’Meara says.

After brainstorming a few ways of making a more equitable solution, O’Meara and his team landed on Supernova’s point of difference: upon creating their profile, each user will designate a social cause as something they support (this can be changed at any time), and any likes they get on their posts pool together with all the other users in that same social pillar. At the end of each month, the ‘votes’ are tallied, and whatever pillar gets the most interaction over the course of the month receives a bigger percentage of Supernova’s ad revenue.

The idea is to foster a different kind of interaction: one built around producing some public good, rather than just facilitating ego and metrics.

“Deloitte did a study, and they think that 80 per cent of millennials and Gen Zs want an ethical alternative ,” O’Meara tells me.

“I want Supernova to bring a brighter, more uplifting, more ethical alternative to the status quo, because I think that what we’ve got is not very encouraging on any of those levels.”

Keep it secret, keep it safe

Beyond moving to more ‘ethical’ alternatives, millennial and Gen Z users are increasingly turning to smaller, more private places on the internet where they can feel protected from the vitriol and surveillance often felt elsewhere.

It might be a Discord community dedicated specifically to a particular video game, for example, or a WhatsApp group where you discuss gardening with members of your local community, and it’s the kind of approach that led to the success, utility and community of sites like Tumblr.

This is called the Cozy Web: a series of mostly private communities that tend to revolve around a shared interest or sub-culture.

Effectively, the Cozy Web is a place where people can escape from the alternative, the Dark Forest: a place where users are constantly being watched, followed, and, effectively, hunted. These aren’t terms that I came up with myself, in my infinite wisdom, but are pulled from tech pundit Venkatesh Rao’s writing.

There are criticisms of platforms that utilise this approach, namely in how their contents can be moderated, but they also allow people to find a small, safe island where people can form friendships around a shared interest: be it a hobby, an idea, or a lifelong condition. Whatever you’re dealing with, there’s likely other people with the same taste willing to chat with you about it.

Compared to the algorithmic deluge of spaces like Facebook, X, TikTok, and YouTube, these spaces are much quieter, but often much more helpful and interesting to users, and typically don’t support much advertising, if at all.

The other benefit to such a platform is that its users, often younger people, are able to feel safer in their relative anonymity.

RMIT’s Buchanan assures me this isn’t just to escape the watchful eye of parents, but also to act on their warnings.

“They’ve been told at school, ‘what you send on the internet’s going to stay there forever’,” he says. “So there’s a move toward smaller-scale networks because it’s a bit more manageable.”

It isn’t that ‘mass social media’ as Professor Buchanan calls them will go away, and that other options will eclipse them, but rather that there will be more places for users to choose from, and more choice in how you want to engage.

Comments

We love hearing from you. or to leave a comment.