Published:

Readtime: 15 min

The Lowdown:

The Scotch Whisky Regulations (2009) | Image: legislation.gov.uk

Every product is carefully selected by our editors and experts. If you buy from a link, we may earn a commission. Learn more. For more information on how we test products, click here.

According to the rule book, Scotch whisky must be a whisky made in Scotland using water and malted barley (and other whole grains on occasion) and is aged for a minimum of three years inside oak casks with an ABV of more than 40 per cent. However, as you’ll soon find out, there’s more to it than that. If you truly want to know your way around uisge beatha (a.k.a. the water of life), you’ll need to know about the regulatory body, the different types, history, regions, and how to drink the dram stuff. Enter our guide, which answers all your questions!

Scotch Whisky Rules

The official Scotch Whisky Regulations (SWR) has an in-depth set of regulations that delve into every minor detail. Here’s what you need to know about the Scotch whisky rules and criteria:

- It must be produced at a distillery in Scotland from water and malted barley

- Should any additional grains (of other cereals) be added to the mash, they must be whole grains

- The distillery must perform the following actions to all of the grains:

- Process them into a mash

- Convert them to a fermentable substrate exclusively by endogenous enzyme systems

- Ferment them by adding yeast only

- The spirit must be initially distilled at an ABV of no more than 94.8 per cent (190 proof)

- The spirit must be wholly matured in an excise warehouse in Scotland inside oak casks for a minimum of three years

- No substances other than water and plain caramel colouring can be added to the spirit

- The resulting statement must have an ABV of no less than 40 per cent (80 proof)

It’s not easy being Scotch, with so many regulations it’s why many Australian whisky brands are shining on the world stage. We spoke to whisky expert Oliver Maruda to get to the bottom of why the regulatory body exists.

“In Scotland, the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA) oversees distilleries to make sure good business practices are being followed, it’s a big reason why Scotch is such a highly respected product all over the world. Other countries have their own regulators for whisky, and Canada was actually one of the first, setting guidelines on age statements and casking to the point that at one point in time, it became the number one spirit consumed in America because the quality was guaranteed,” said Oliver Maruda, a whisky expert and co-founder of The Whisky List.

“Unfortunately, not every country has these guidelines, and in some parts of the world, you can find the word ‘whisky’ stamped on everything from rum to aged rice wine. Having these purity laws in Scotland gives consumers assurance they‘re buying a bottle of whisky that’s made with heritage, practice, and skill.”

While the SWR’s requirements may seem over the top, they still leave plenty of room for experimentation. For instance, Scotch whisky can be either chill-filtered or non-chill-filtered. Also, the type of cask in which the whisky is aged can vary, though the spirit is most often aged inside ex-bourbon barrels. After that, the drink can undergo additional maturation (aka finishing) inside sherry casks, port casks, rum barrels, or whatever the distiller or producer has in mind. So what about the different types?

Types of Scotch Whisky

These are the five different types of Scotch:

| Types of Scotch whisky | |

|---|---|

| Single Malt | To qualify as single malt, the Scotch must be made from a mash of 100 per cent malted barley and distilled at a single distillery by way of a pot still distillation process. |

| Single Grain | Despite the name, single-grain can incorporate other whole cereal grains (malted or unmalted) into the mash. The drink must be distilled at a single distillery and it can be distilled continuously in continuous stills or column stills. |

| Blended Malt | A blend of single malt from at least two different distilleries. |

| Blended Grain | A blend of single-grain from at least two different distilleries. |

| Blended Scotch | A blend of single malt and single grain Scotch whiskies. |

The argument between single malt and blended scotch whisky has been ongoing for years. To get to the bottom of the discussion we asked experts for their thoughts on the matter, but when you consider an estimated 90 per cent of Scotch whisky sold is a blend the consumer demand for this cheaper bottle tells you there’s probably nothing “wrong” with drinking blended whisky at all! Let the single malt purists be purists and the dram drinkers enjoy whatever they want we say.

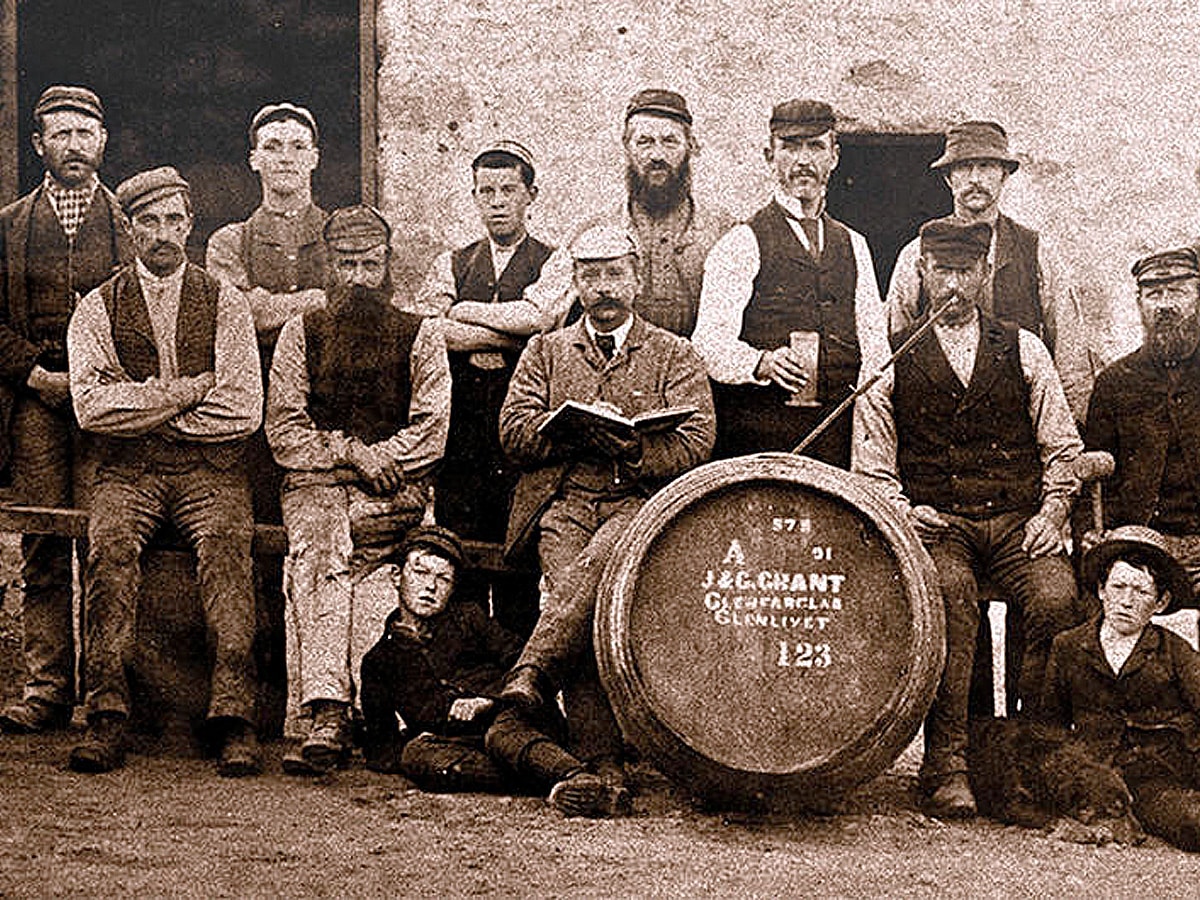

History of Scotch Whisky

Without taking hours of your life, Scotch whisky evolved from a drink called uisge beatha (don’t try to pronounce it, it’s Gaelic–you might hurt your voicebox), which means “water of life” (not dissimilar to France’s eaux de vie). Though spirits had been distilled in Europe for some time, and more rudimentary alcohol to some extent, in northern Africa, before that, whisky was a different beast. Scottish whisky found early popularity thanks to King Henry VII, who, in 1495, gifted eight bolls (that’s a lot) of malt to one Friar John Cor, to distil around 1,500 bottles of uisge beatha.

This is the first recorded mention of the good stuff in the history books (The Exchequer Rolls of Scotland to be precise), but we can assume that if he was capable of making 1,500 bottles of the stuff, ol’ mate John Cor already had distillation down to fine art, as, likely, did his forebears, and many others.

When the UK Parliament, in 1823, introduced a new way of taxing whisky, however, (legal) production doubled overnight. Eight years later, the first column still was born, which improved both quality and output for grain whisky, which opened the door to large-scale blending. Though here we’re focusing on Single Malts, the proliferation of blended Scotch was one reason the spirit enjoyed widespread popularity–this was arguably the start of Scotch whisky as we know it today.

Continuing Popularity Today

From Johnnie Walker to The Macallan, the long list of Scotch whisky brands that have infiltrated the global market is nothing short of incredible. Some bottles have even fetched up to £1,452,000 at auction.

Over the years, the spirit has become one of the leading exports for Scotland, with the Scotch Whisky Association revealing that the export value of Scotch whisky in 2021 was £4.51 billion, up £705 million compared to 2020. On average, 44 bottles of Scotch whisky are exported every second, thrown from all parts of the country to a massive international legion of fans, hailing from regions as far-reaching as the USA, France, Australia and even Latvia, which accounted for £176 million of Scotch exports in 2020.

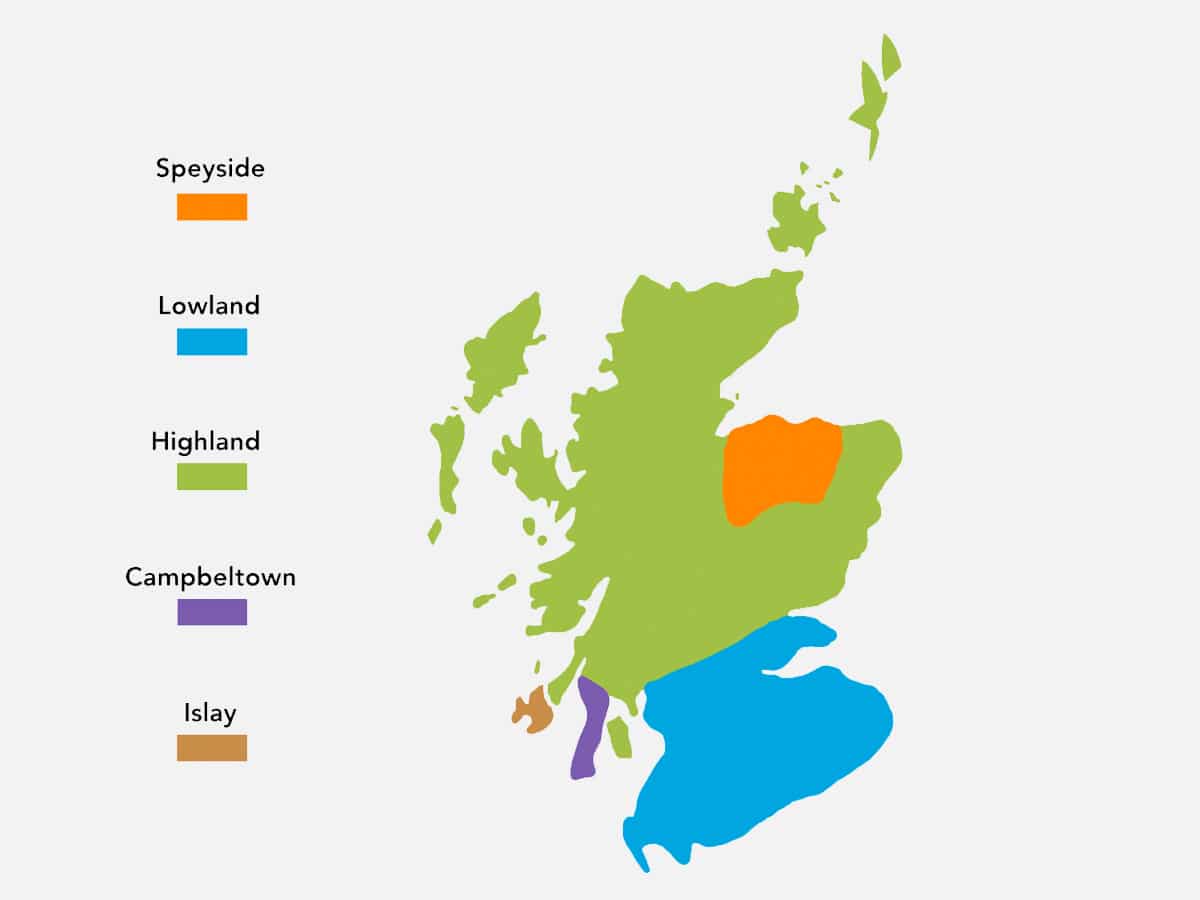

According to Scotch expert and Crown Resorts venue manager Aaron Shuttleworth, each region of Scotland is responsible for pioneering its own versions of the spirit, which in turn has garnered a unique and engaged fanbase.

“Whilst there are subtle variations in production methods from distillery to distillery and region to region, there are characteristics you’ll generally find that define a particular designation,” he explains. “Highland scotches tend to be richer and fuller styles with notes of malt, oak, fruit cake and heather coming through. Further south in Speyside, the whiskies are more delicate and generally absent of any peat, with notes of apple, vanilla, nutmeg and dried fruits making them approachable to newcomers to whisky.”

“The Lowlands produce a lighter style again and are unique in that they were once all triple distilled. Grass, toast, and honeysuckle are predominate tasting notes,” Shuttleworth continues. “Islay is best known for its use of local peat to create unique malts, channelling notes of seaweed, brine, smoke, iodine and rich fruit. Finally, The Islands surrounding Scotland aren’t technically classified (aside from Islay) and each has its own distinctive style, with heather, honey and salinity present in most examples. There are countless outliers and curve-balls to all of these regions and surprises to be found where you least expect.”

Join Our Exclusive Community!

WINNER– Media Brand of the Year, 2025

WINNER– Website of the Year, 2024

How Scotch Whisky is Made

The very basic recipe calls for barley or grain, yeast, and Scottish water. We’ll stick to single malt for our explainer below as it can get quite exhausting and confusing when you add grain to the process.

Malted barley is barley that has been allowed to germinate slightly, triggering enzymes, so that the starches may develop into sugar during the mashing process. This is then dried and ground into a coarse powder known as “grist,” before having hot water introduced to it: starting out at around sixty degrees and incrementally nearing boiling point. This dissolves the sugars and is known as the mash.

After mashing, this liquid is now known as the “wort,” which is cooled, and yeast is added, which in turn starts to convert the sugars into alcohol. Congeners are also produced, which add flavour to the whisky. This “wash,” which is very similar to an unhopped beer, froths as carbon dioxide is produced–this lasts around two days, by which stage the wash is between six and eight per cent alcohol by volume (ABV).

This now goes into a copper pot still, the shape of which has a large impact on the flavour of the final product. Copper pot still is preferred for its neutrality when in contact with alcohol. Heat is applied (enough to vaporise the alcohol, but not the water) and the vapour is run through the “swan’s neck”, where it condenses over coils filled with running cold water. The first run through the still produces a clear spirit at approximately twenty per cent ABV. The second run, which captures the “heart of the run”, that is, the pure, clean, centre part of the distillate, is over sixty per cent ABV. The “heads” (the first part that runs off the still) and the “tails” (the last) are recirculated into future batches, to ensure any of the remaining hearts can be extracted.

Once the new-make spirit has been distilled and the distiller is happy with the liquid, it gets placed in oak casks, primarily those previously used for bourbon or sherry, and left for a minimum of three years (though most whiskies with an age statement will age for significantly longer than this). Much of the liquid evaporates in this time (this is known as the “angel’s share”), while the flavours of the oak (and whatever was in it beforehand) slowly impart themselves upon the liquid in the cask.

Unless it is a single cask batch or bottled at cask strength, the liquid that comes off the casks is then married to taste, and distilled water is added to the Scotch whisky, to achieve the desired ABV (this must be a minimum of forty per cent). And there you have it.

Know the Different Regions

There are five (unofficial) Scotch whisky regions, they’re as follows:

- Speyside: Home to around 60 per cent of the country’s whisky distilleries, Speyside is known for its sherry cask matured drams and well-rounded single malts making it the best place to start your whisky-tasting journey. Every now and then you’ll come across the odd smoked bottle, however, you’ll have to look for it because brands like The Macallan, Glenfiddich, Aberlour, and The Balvenie dominate this region.

- Islay: If you want to taste the equivalent of sucking on the nearest chimney, head to the Isle of Islay. It takes appreciation to understand the meaning of smoky whisky, however, once you unravel this beast you’ll long for the stuff. Brands like Laphroaig, Lagavulin, Ardbeg, Bowmore, and Bruichladdich dominate with flavours of chocolate and sea salt.

- Highlands: The largest producing whisky region in Scotland, the Highlands offer similar flavours to the Speyside brands with flavours of sweet sherry and buttery vanillas, however, note that Eastern and Southern Highlands tend to be a tad lighter on the palate than those found in the North. Western Highlands distilleries such as Oban, find a peatier influence if that’s what you’re after.

- Lowlands: Taking a bit of Speyside under its belt the Lowlands offer peaty drams with maritime notes of salt and brine. An interesting note is although each distillery in the region used to practice triple distillation, Auchentoshan is the only one that still employs the method and brings citrus flavours to the table.

- Campbeltown: Only three distilleries remain in Campbeltown which makes it quite a unique region: Springbank, Glengyle, and Glen Scotia. You’ll find flavours of dried fruit, vanilla, and toffee, which are fairly standard, but with the addition of a pungent body, they bring plenty to the table.

Does the region matter? Well, it’s more a matter of personal preference than anything else. While certain regions have slightly different practices in terms of production (for example, the burning of peat on Islay will produce a smokier whisky), the essential recipe for whisky is used unanimously across the different regions of Scotland.

Like wine, regionality will affect the final product in terms of terroir, which is reflected in the water used, barley harvested and malting process, however the production methods remain fundamentally identical between distilleries (much like Champagne, Scottish whisky is a highly regulated product to produce, with many legislative controls ensuring quality and consistency).

How to Drink Properly

The simplest rule is: as you like it. While purists will turn their nose up at the slightest encroachment on their precious spirit, most sensible connoisseurs or bartenders will proffer that if you’re paying for it, you can have it however you like. While whisky and coke will seldom be improved with a more expensive dram such as a single malt, however, there are ways to taste a beautiful premium spirit that you should definitely try out before adding your favourite mixer.

Firstly, choose a great whiskey glass, preferably a “Glencairn glass”, to get amongst the delicious aromas and flavours that you’ll find in a single malt from Scotland. Start by checking it’s clean and free of any other scents (dishcloths are notorious for leaving a faint whiff of detergent) – the best way to do this is to pour a small amount of whisky into the glass, swirl it around and then pour it out. The importance of using a tasting glass (aka tulip) comes down to its unique shape, which focuses the delicate aromas of the contents toward the nose, unlike a rocks glass.

Pour your whisky into the glass and bring it to your nose. It’s incredibly important to smell the whisky with your mouth open (this will bring more fresh air into your olfactory and help to overcome the “hot” smell of the booze). If it is a particularly strong whisky (i.e. it has a cask-strength ABV), you may want to add a few drops of water, or let the more volatile elements breathe for a few minutes, though it’s always a good idea to try it as is first, before meddling with it.

Whisky is always best tasted around thirty-five per cent ABV, so a teaspoon of water will make a huge difference in helping to open up some of the richer, oiler flavours in the glass, as well as display some of the more fruit-driven characteristics.

Alternatives to Scotch Whisky

The best alternatives to Scotch whisky are found in Japan, Ireland, Australia, and more recently, India. However, its Japanese whisky has become globally recognised for its quality and provenance, in fact, some of the brands (from The Yamazaki and Karuizawa) have fetched more than £363,000 at auction. On the other hand, Ireland offers a relaxed ruleset compared to Scotland and the result is a new age of whisky that experiments with younger age statements barrelled in sweet wine barrels. The same can be said for the best Australian whisky brands, specifically those from Tasmania that have won awards against some of the world’s best. Of course, you always have your American bourbons, ryes, and Tennessee whiskey.

What is the Difference Between Scotch and Whiskey?

Whisky made in Scotland a.k.a. ‘Scotch’ must adhere to a strict set of rules. For one, it must be aged for a minimum of three years inside oak casks, made from Scottish water and malted barley (and other whole grains on occasion) and bottled with an ABV of more than 40 per cent. On the other hand ‘whiskey’ carries no age statement and adheres to a less stringent set of rules depending on those set by the country of origin.

Comments

We love hearing from you. or to leave a comment.