Published:

Readtime: 11 min

Every product is carefully selected by our editors and experts. If you buy from a link, we may earn a commission. Learn more. For more information on how we test products, click here.

It’s not uncommon for most of us to come across dividend franking in one way or another and to be left scratching our heads. We were all bombarded with claims and counter claims around franking credits during the last federal election and left wondering who to believe.

Even the jargon can be confusing. Terms like dividend imputation, franked and unfranked dividends, imputation credits, and so on, float around but do not convey a lot of meaning for many of us and leaves us wondering what it all really means.

So, we have put together this short guide to help you understand better what dividend franking is, how it works, and what it might mean for you.

We know most of this can be boring stuff, but trust us, getting some understanding will be useful. And if you have already dipped your toes into the world of share investments, this is up your alley.

Ending Double Taxation of Company Dividends

First, a little history on the world before dividend franking and its introduction.

Companies are taxed on the profits they make and typically pay dividends out of their after-tax profits.

Prior to 1987, however, when a company paid a dividend to shareholders out of their after-tax profits, the shareholders had declared the dividends as part of their taxable income and hence pay tax on the dividends at their personal marginal tax rate. This was despite the fact that the company had already paid tax on the profits from which the dividends were paid.

In other words, dividends were double taxed.

In 1987, to put an end to this ‘double taxation’, the then Labor Government led by Bob Hawke as PM and Paul Keating as Treasurer introduced what was called a dividend imputation or franking system to make sure that company profits paid to investors were only taxed once.

Keating’s dividend imputation system worked by attaching a tax credit, called a Franking Credit, to each dividend. To avoid double taxation, the franking credit attached to each dividend was set at an amount equal to the tax the company had already paid on the profits from which the dividend was paid. WE show how this works below.

When companies pay dividends to shareholders from monies that they haven’t already paid company tax on, such dividends are treated as unfranked dividends under the new franking rules. The unfranked dividends do not have any franking credits attached, as no company tax has been paid, and shareholders pay tax on the unfranked dividend at their marginal tax rate.

The Nitty Gritty of Dividend Franking

Let’s cut through the complexity and look at a simple example based on the following hypothetical scenario: XYZ Company makes a $100 profit and pays company tax of 30% on the profit, i.e. $30 of company tax. The company then pays out the remaining $70 of its profit as a dividend to its shareholder, who we will call Trevor.

Under dividend franking, when shareholder Trevor receives the $70 of dividend, he also receives a franking credit equal to the tax paid by the company on its profit, namely $30.

Let’s look at how this then plays out in Trevor’s preparing his tax return.

Step 1. The $30 franking credit is added to Trevor’s $70 franked dividend and the $100 total ($70 + $30) declared as part of his taxable income.

Step 2. The $100 declared by Trevor is then taxed at his marginal tax rate, but this tax is then offset by the $30 franking credit.

If Trevor has a 30% marginal tax rate, he will pay $30 tax on his $100 of grossed-up dividend, but the $30 of franking credit offsets this tax, so Trevor would end up paying no tax on his $70 dividend.

If Trevor’s marginal tax rate is 45%, his tax on the grossed-up $100 dividend is $45, but the $30 franking credit is a tax credit and Trevor would end up only paying the extra $15 to the Tax Office.

By Trevor being able to deduct the tax paid by the company from the tax due on his dividend, double-taxed on the $30 tax on the $100 of company profits is avoided.

How You Can Benefit from Dividend Franking

You may have already dipped your toe into share investing or are thinking about it, so understanding the benefits of dividend franking is already relevant. It is certainly a wise and sensible thing for everyone to build up some investment savings if they can. And as part of that, buying shares in solid reliable companies that pay fully franked dividends can make good sense depending on your circumstances.

In any event, everyone with an industry or workplace superannuation account (and that is everyone who is employed) is already benefiting from dividend franking through share investments in their superannuation fund, unless of course if they have chosen to put all their super into non-share investments.

So, having some understanding of how dividend franking works and how it might impact or benefit you now or in the future is of relevance to most people.

While dividend franking has benefits for all shareholders irrespective of their taxable income, the benefits do vary depending on an individual’s marginal tax rate.

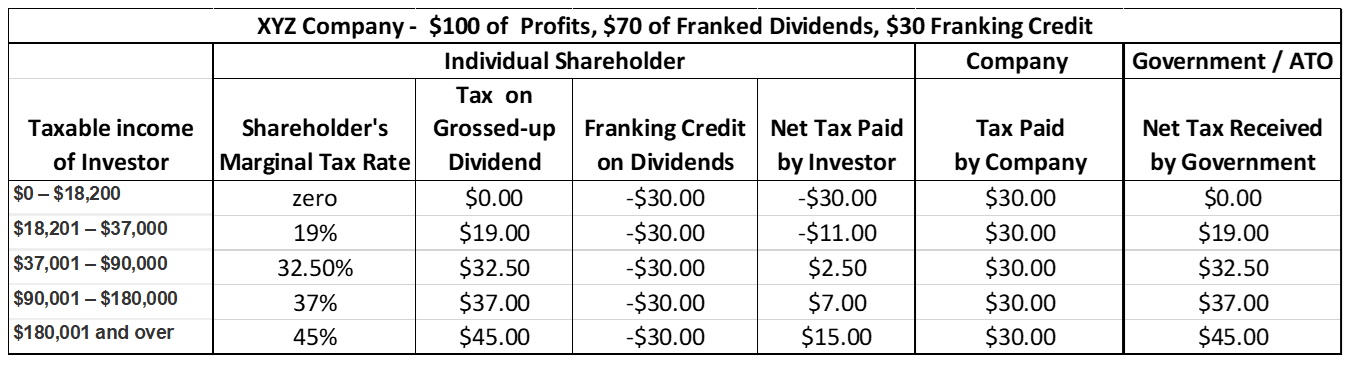

The Table below looks at how dividend franking benefits different shareholders according to their taxable income and illustrates this using the earlier hypothetical XYZ Company example. It shows the tax collected on the $100 of company profit at the shareholder and company level and the net tax collected by the Australian Tax Office (ATO).

As you can see, for shareholders with taxable income within the current top three income tax brackets (i.e. those with a marginal tax rate of 32.5%, 37% and 45%), they will still pay some tax on their dividends but much less than under the pre-Keating arrangements of double taxation.

For example, the Table above shows that a shareholder with taxable income say of $80,000 (i.e. within the current 32.5% marginal tax bracket, would only pay $2.50 of tax on their $70 of dividends form XYZ Company. But prior to dividend franking their tax would have been $22.50 ($70 x 0.325). That is a saving of $20 of tax compared to the pre 1987 double taxation of dividends.

Shareholders with taxable income within the bottom two taxable income brackets (ie with marginal tax rates of zero or 19%), actually end up with a tax credit after receiving franked dividends. AS the Table show, shareholders with taxable income below $18,200 (which picks up many zero taxed retirees) dividend franking of the $70 dividend results in a $30 tax credit for the shareholder. Those in the 19% marginal tax bracket, end up with an $11 tax credit.

Keating’s Franking Could Only Reduce a Tax Bill to Zero

An important feature of the Hawke / Keating dividend imputation scheme was that any franking credits received by shareholders could only be used to cut or reduce a shareholder’s tax bill. That is, shareholders could only use franking credits up to the point of reducing their total tax bill to zero. Once a tax bill was reduced to zero, any excess franking credits left over were of no value and could not be used to get a tax refund.

For example, for shareholders with taxable income in the lowest tax bracket, in the Table above, the $30 tax credit resulting from the franked dividend could only be used to reduce the shareholder’s total tax bill to zero. Any excess credit was ‘worthless’ and was not refunded.

The Howard and Costello ‘Gift’

In 2000, the John Howard and Peter Costello Liberal Government changed the game and made franking credits fully refundable. That is, shareholders could now get a cash refund for any excess franking credits left over after reducing their tax liability to zero. It represented a generous ‘gift’ for many low-income shareholders, costing the budget at the time an estimated $550 million per year.

In 2007, however, the Howard / Costello refund of excess franking credits policy really kicked into gear for retirees. The Government decided to make benefits, from a taxed superannuation fund, tax free for people aged 60 and over when benefits were received either as a lump sum or as an income stream. This really stoked the fire and resulted in many more retirees now receiving tax refund cheques for ‘excess’ franking credits and many more switching investment strategies towards franked dividends.

Now You See It Now You Don’t

If shareholder Trevor, in our hypothetical example, is a self-funded retiree holding his XYZ Company shares in a Self Managed Superannuation Funds (SMSF) which is in pension phase, the $100 of grossed-up dividends will not be taxed in the fund. But Trevor’s SMSF will also receive a cash refund cheque for the $30 of excess franking credits that were not needed to be used to zero out Trevor’s SMSF’s tax bill.

As a result, the $30 of tax paid by the company ‘disappears’ from the Government’s coffers and is in effect given to Trevor’s zero taxed SMSF. Hence, no tax ends up being collected by the government on the $100 of company profits.

Hence, when zero taxpayers receive franked dividends, the company profits supporting those dividends also end up being zero taxed. That is, dividend franking together with the refund of the excess franking credits, in this case, has not only prevented the double taxation as intended, but it has also resulted in the company profits, from which the dividends are paid, being zero taxed. Which is why the refund of excess franking credits was not allowed when Keating first introduced dividend franking in 1987.

That said, Trevor and other similar zero taxpayers are simply abiding by the rules and reaping the intended benefits of paying no tax while also getting cash refund cheques for any franking credits they receive with their share dividends.

Little wonder such zero taxpayers love franking credits and that franked dividends have quickly become a retiree favourite.

So, no surprise that the annual cost to the budget of refunding excess franking credits has ballooned tenfold to some $5.9 billion, based on Federal Treasury analysis.

Watch This Space

It’s worth keeping in mind the laws and policy regarding taxation, including dividend franking, and superannuation are regularly reviewed.

The concern with the growing cost to the budget of tax benefits attached to superannuation, including the cash refund of excess franking credits, triggered the Malcolm Turnbull Government, in 2017, to limit the amount of tax-free superannuation that those over 60 of age could hold to $1.6 million.

Beyond the growing cost to the budget, there are also growing concerns relating to fairness, given that most of the excess franking credits refunds are going to wealthier retirees.

According to the Parliamentary Budget Office, only 8% of Australian taxpayers benefit from any refund of excess franking credit. And for Self Managed Superannuation Funds, 82% of the refunds go to retirees with fund balances of over $1m, with slightly more than half going to those with balances over $2.4 million. At the very top end, wealthy retirees are individually receiving refund cheques of over $100,000 each year.

It was concern relating to the costs and fairness that led to Labor’s failed proposal to wind back the refund of excess franking credits, at the last election. However, given the election result and continued widespread opposition from retirees and others to the proposal, Labor has said it has now dropped the policy.

The reality is that there are many self-funded retirees who have relatively low-income and have become dependent on the refund of excess franking credits – as have many pensioners looking for a little extra income.

From a broader community and budget policy perspective, however, the fact that no tax is being collected from many billions of corporate profits when excess franking credits are refunded to zero taxpayers will remain an issue given the enormous budgetary challenges flowing from measures to address the fallout from the COVID 19 pandemic.

Given that the annual budget costs of the refund of excess franking credits are projected to grow to around $8 billion within the next decade, we may well see the winding-back refund of excess franking under consideration again.

That said, dividend franking itself to prevent the double taxation of corporate profits looks here to stay.

Article by Dr Noel Purcell

Dr Purcell has had a long career in banking, finance, and public policy. Before retiring, Noel spent 23 years in senior executive roles with Westpac Banking Corporation both in Australia and Japan. Prior to that, he served at senior executive levels within the Federal Public Service, including the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Office of National Assessments, and the Australian Bureau of Statistics. He has also served on several advisory and not-for-profit bodies including as Global Chair of the internationally recognised Caux Round Table.

Comments

We love hearing from you. or to leave a comment.