Published:

Readtime: 4 min

Every product is carefully selected by our editors and experts. If you buy from a link, we may earn a commission. Learn more. For more information on how we test products, click here.

For decades, Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson has played gods, superheroes, and other (mostly indestructible) action heroes. In The Smashing Machine, Benny Safdie’s hefty MMA biopic, Johnson displays a new kind of strength as Mark Kerr—the MMA fighter and UFC heavyweight whose early stardom was consumed by addiction and fame.

Johnson all but disappears in the role of a competitor swollen by steroids, dulled by painkillers, and one loss away from collapse. It’s the boldest performance of his career, and it’s also his best.

A Ringside Seat

Benny Safdie brings the same jittery energy to The Smashing Machine that made Uncut Gems and Good Time so electric. He’s flying solo here for the first time after an amicable parting of ways with his brother Josh, who has his own film, Marty Supreme, coming in December.

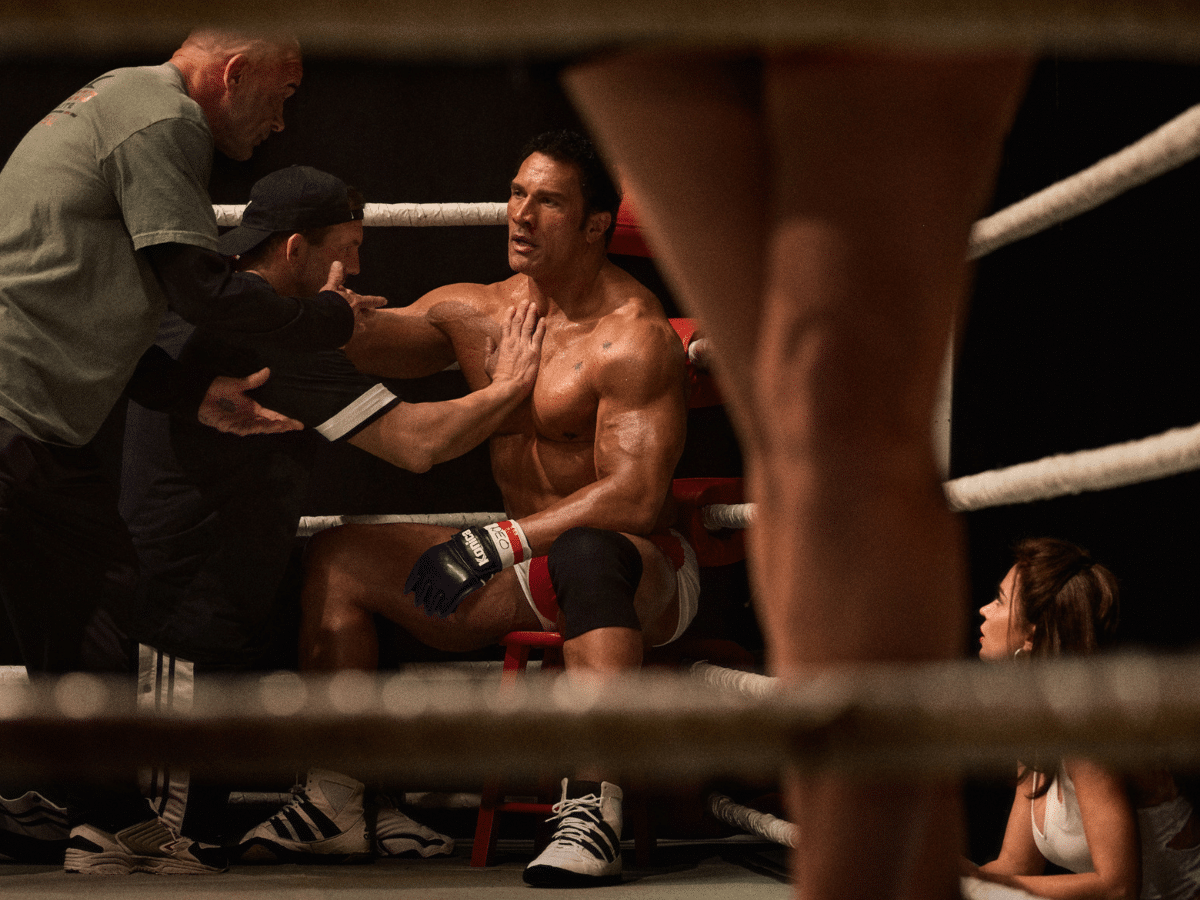

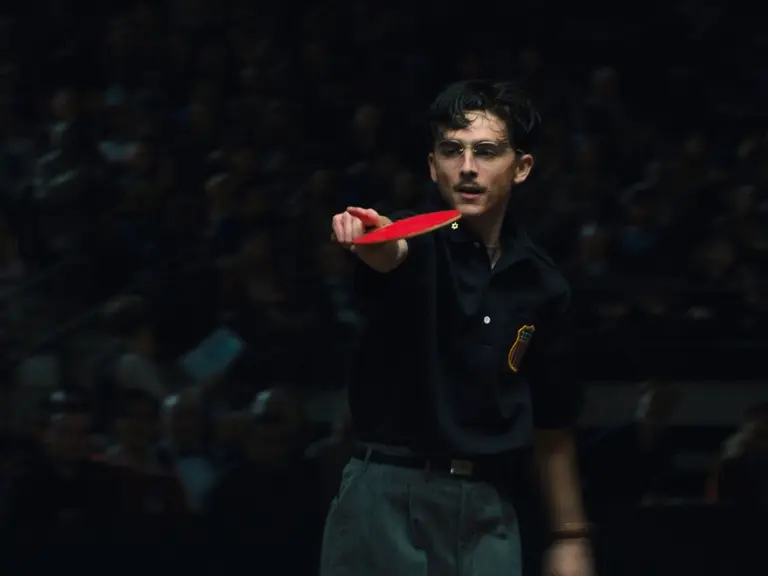

Together with cinematographer Maceo Bishop, Safdie develops an approach of the camera as a ‘spectator’, with the lens never really entering the ring. It hovers outside the ropes—trapped among screaming fans, flashbulbs, and flying sweat. There are no slow-motion knockouts, only long takes of captured chaos, which meant casting real fighters like Ryan Bader and Oleksandr Usyk that understand the ins-and-outs of the necessary physicality.

Unlike most sports movies, Safdie is not preoccupied with the wins, but with what you can learn about a person from their losses. What happens when the crowd stops cheering, or when the body stops working?

From Icon to Everyman

More character study than sports movie, The Smashing Machine is a biopic in the vein of A24’s The Iron Claw, aiming to find the men behind the muscle. Safdie wisely constructs a solid narrative covering only a couple of years. It doesn’t seek to tell Kerr’s entire life story and that’s a strength.

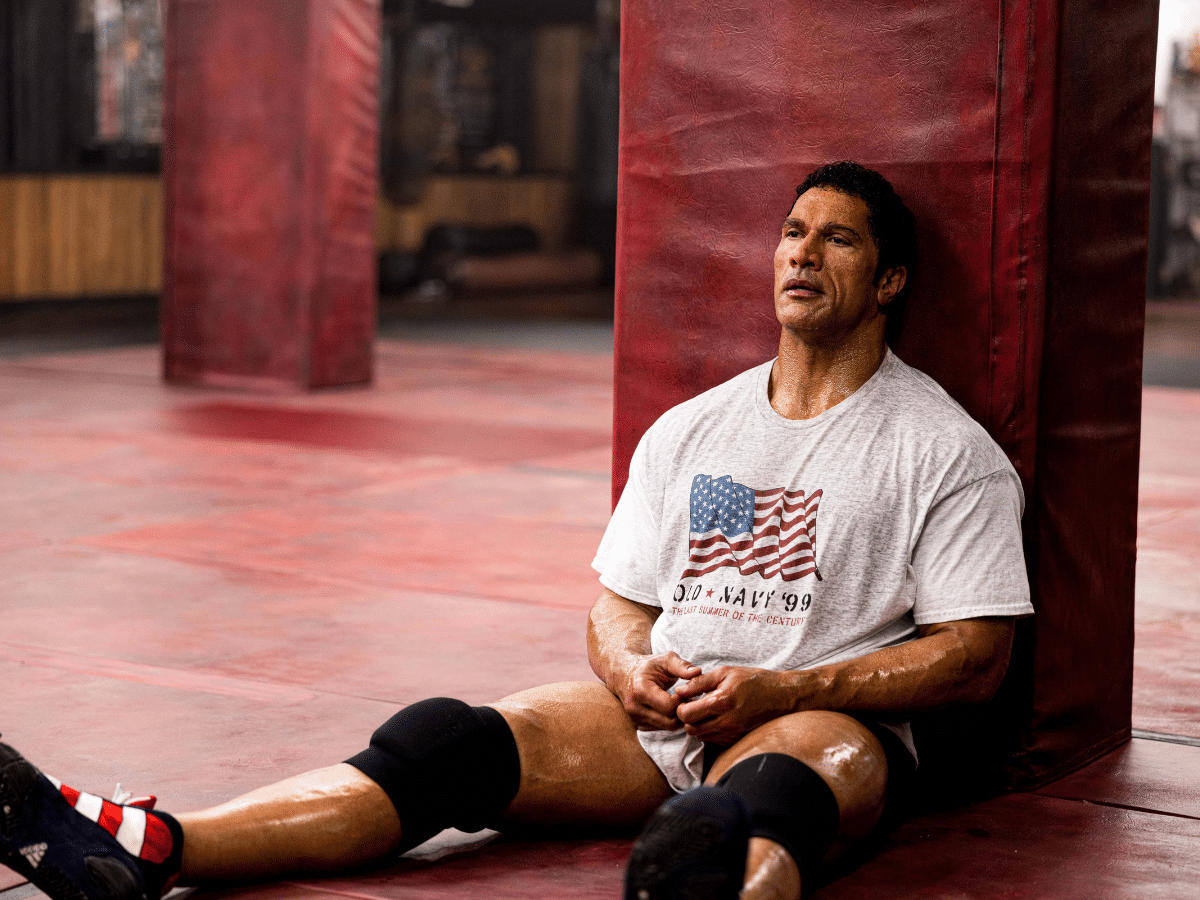

Credit goes to hair, make-up and prosthetics, which nail Kerr’s puffed look, but the transformation goes deeper as Johnson moves slower, breathes heavier, and finds a quality in Kerr that we’ve never seen in the Rock. Safdie insisted on no doubles, which required the actor to train, spar and absorb some real punches. As a story of addiction in its many forms, Johnson sells the cycle of the high, the shame, the bargaining and the weakness that ultimately comes with dependency.

The Other Octagon

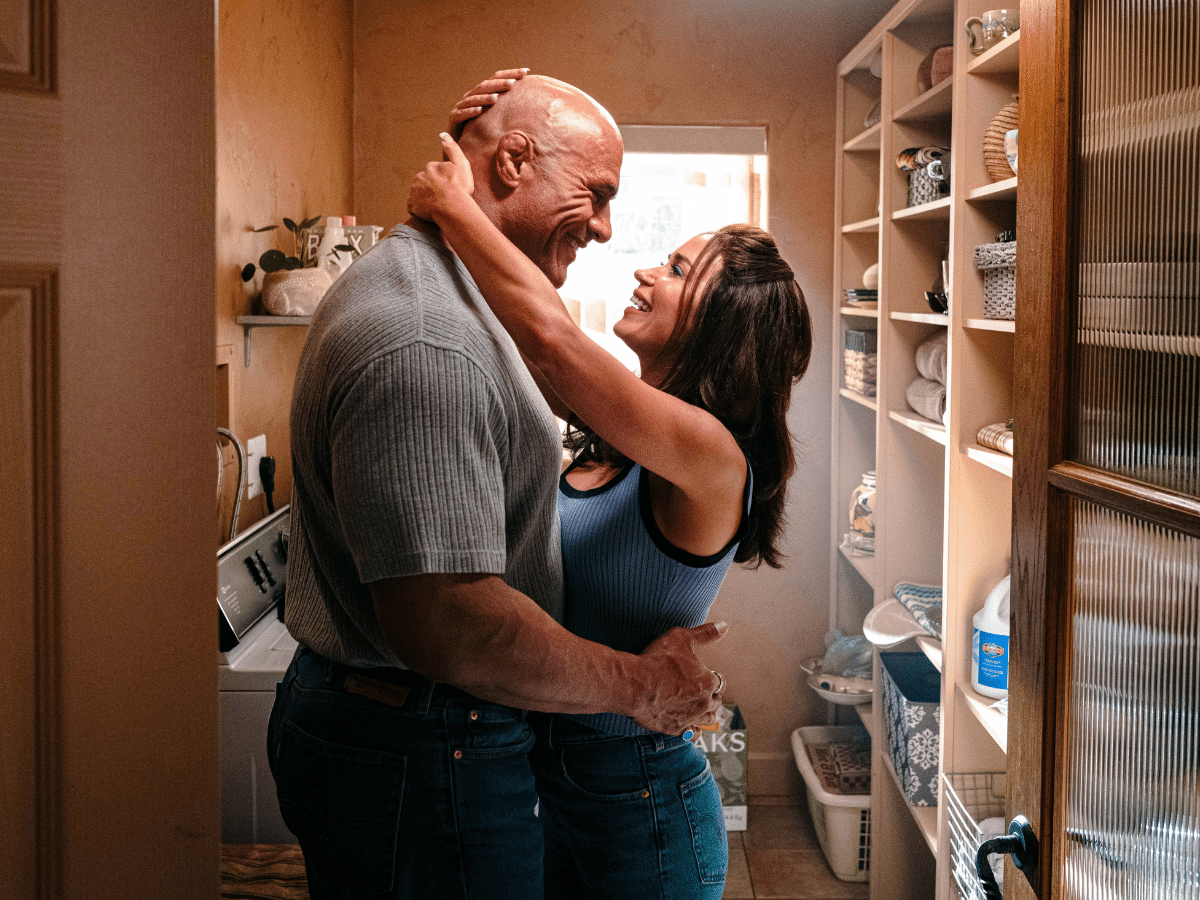

As Kerr’s girlfriend Dawn Staples, Emily Blunt is just as vital as Johnson. She’s not so much the long-suffering partner or moral compass that female characters tend to fill in this kind of movie, but another combatant and every bit Kerr’s match.

Safdie designed their home to feel like another arena—shooting domestic fights with the same intensity as title bouts. The result is an honest depiction of a toxic love story: two people who really shouldn’t be together but can’t seem to quit. Blunt is always on top form, and here she delivers a raw performance, finding a quality in Staples that further expands her considerable range.

The Final Bell

The Smashing Machine is less a rise-and-fall sports movie than a character study about the toll of addiction and self-punishment on the body, the mind and the heart. It’s also an ode to the pioneers of UFC, who bled before there was real financial skin in the game.

The costumes, production design and music provide specific period notes of the late 90s and early 2000s, which are complemented by Safdie’s choice to move from VHS quality to 16 mm and ultimately 65 mm, all of which gives the film a scope and texture that really works on the big screen. Johnson and Blunt find an engaging fragility in a solid biopic reminding us that the hardest fights often happen beyond the ring. ★★★★☆

Comments

We love hearing from you. or to leave a comment.