Published: Last Updated:

Readtime: 7 min

Every product is carefully selected by our editors and experts. If you buy from a link, we may earn a commission. Learn more. For more information on how we test products, click here.

For four decades, Canberra has talked about high-speed rail. This week, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was finally asked the simple question: is it actually happening? Answering with an enthusiasm that’s been missing from past attempts (Albo is a former transport and infrastructure minister after all), he made it clear it’s coming, but he won’t be PM when it arrives.

It’s a generational build. And for the first time in a while, there’s a government with both the numbers and the appetite to try.

So is it finally happening? Most likely, yes. Not in one sweeping Brisbane to Melbourne line, but in stages, starting with Newcastle to Sydney. And with the High Speed Rail Authority operating since 2023, $500 million committed to corridor planning, Infrastructure Australia backing development, and an additional $230 million from the Albanese government, there’s finally a structure behind the idea. May’s budget will tell us whether planning turns into long-term funding.

Plenty will say we’ve heard this before. More than $150 million has been spent studying fast rail since the 1980s. Reports stacked up. Business cases came and went. We never got beyond the plans.

Now we need to see a shovel in the ground, even if someone else cuts the ribbon. That’s why this one feels different.

What It Actually Changes

What we’re talking about is Newcastle to Sydney in about an hour. The Central Coast 30 minutes from either end. Lake Macquarie closer to the CBD than parts of Western Sydney are right now.

It’s getting home before dark. It’s saying yes to a job in the city without moving your family. It’s turning what feels like a regional decision into a weekday commute.

Australia’s population has passed 27 million, and roughly 60 per cent of us live along the Brisbane-to-Melbourne corridor. By 2051, that corridor alone is projected to hold around 28 million people. Our roads are filling up. Airport queues are getting longer. Sydney to Melbourne alone carries close to ten million passengers every year. Growth at that scale demands more than extra lanes and departure gates.

How Big Are We Talking?

If it all goes ahead, it will likely become the most expensive infrastructure project Australia has ever attempted.

The 2013 federal study put a Brisbane to Melbourne line at $114 billion in 2012 dollars. Adjust that to today, and you’re talking north of $150 billion. The Newcastle-to-Sydney section alone would involve roughly 191 kilometres of new dedicated track split between surface track and bridges, with 115 kilometres running through tunnels.

The current business plan involves a two-year development plan allowing construction to begin in 2028, the same year as the next federal election.

Provided investment approval is granted, the high-speed rail line would connect Newcastle, the Central Coast, the Sydney CBD, Parramatta and the Western Sydney Airport by 2042.

Fresh analysis from the High Speed Rail Authority reportedly puts the cost somewhere between $70 billion and $90 billion. That would make it the most expensive single piece of federally funded infrastructure in Australian history.

For comparison, WestConnex pushed past $45 billion. Sydney Metro sits around $35 billion. Melbourne’s Metro Tunnel is roughly $12 billion. Queensland’s Cross River Rail is about $5.4 billion. Sydney is also building a second international airport at Badgerys Creek, with the first stage costing more than $5 billion. But they’re all single-city builds. This would be one corridor between two cities, and it could cost more than all of them.

Driving from Newcastle to the Sydney CBD can take close to two hours on a clear run, longer once the M1 clogs up. The current intercity train can stretch well past two hours. An hour on a dedicated high-speed line is shorter than many commutes across Sydney today. And it’ll bring with it a $250 billion boost to the national economy and create more than 99,000 jobs. How good.

The Money Question

Australia has been world class at studying high-speed rail. Building it is another story.

Very few city-pairs globally generate enough demand to make high-speed rail stack up on fares alone. Tokyo to Osaka works. Paris to Lyon works. They move well over 20 million passengers a year.

The Sydney to Melbourne air route carries nine to ten million passengers a year. It’s one of the busiest air routes in the world. And yet, it’s rarely quick once you factor in airport lines and the terminal shuffle either side of a one-hour flight. It’s not always cheap either. The route works, but it’s hardly frictionless.

But busy doesn’t mean it pays for a bullet train on its own. It’ll take serious government money and a lot of willpower. Especially when the first 191 kilometres alone could cost up to $90 billion.

NSW has indicated it will not commit funding at this stage, meaning the federal government would likely carry most of the burden.

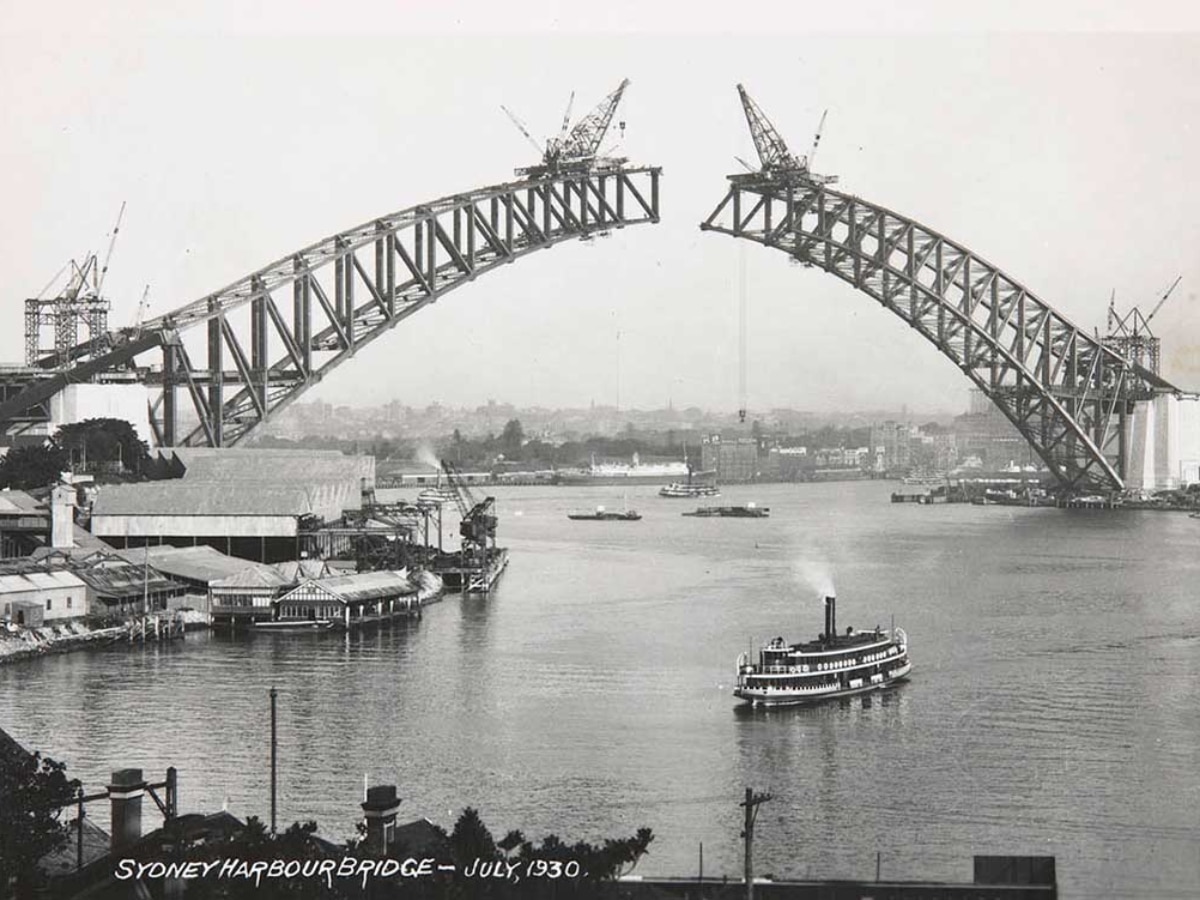

Big infrastructure projects are rarely about making money. The Snowy Mountains Scheme wasn’t judged purely on electricity sales. The Sydney Harbour Bridge was attacked as too expensive before it opened. Britain’s HS2 shows what happens when costs blow out and political consensus wobbles mid-build. The Interstate Highway System in the US wasn’t built because toll revenue stacked up in year one. Each reshaped how people lived and how cities expanded. High-speed rail outdoes them all.

But don’t expect a station in every regional town. Speed is the whole point. The faster you want it to run, the fewer stops you can make. Add too many, and it’s no longer high-speed rail. It becomes something else.

That’s the trade-off. And if we get it right, it’s powerful. A true high-speed spine between major centres doesn’t just save time. It changes where people are willing to live, where businesses invest, and how tightly this stretch of coastline functions as a single economy.

Built properly, it’s a different map.

We’ve Been Here Before

Australia has been talking about high-speed rail since the 1980s. The Very Fast Train proposal came and went. Speedrail between Sydney and Canberra stalled. The Gillard government commissioned a two-stage study that landed on a $114 billion price tag. Momentum faded each time.

We’re good at commissioning reports. We’re less good at protecting corridors and putting shovels in the ground.

Because the hard part has never been digging tunnels. It’s been keeping governments aligned long enough to finish what they started. May’s budget will tell us whether this is a press conference or a project.

On The Right Track

When the Sydney Harbour Bridge opened in 1932 with six traffic lanes across the harbour, it stopped being controversial. The benefits were obvious.

If Newcastle to Sydney runs in an hour in the late 2030s, it’ll likely feel the same way. People won’t remember the arguments. They’ll just use it.

Planes won’t disappear. Traffic won’t vanish. But the way the east coast fits together will shift. A Newcastle address won’t feel so “regional” anymore. A Central Coast commute won’t mean compromising your life. A Melbourne meeting won’t automatically force you into the airport at 5am. Where you live won’t be tied so tightly to where you work. The map doesn’t change. Your options do.

The real question is whether we’re ready to build for the country we’ll be in 20 years, not just the one we’re arguing about this week.

Comments

We love hearing from you. or to leave a comment.